Tudor Muşatescu, a Romanian playwright, once wrote, “The glory is not ephemeral. Ephemeral are only those that have it.” Is IBM the exception that proves the rule? As a matter of fact, Big Blue turned 100 this month, and according to its financial records in a pretty good shape. For instance, IBM’s market value passed Google’s last February. However, these 100 years have not always been a bed of roses for IBM, specially the last 30 years. In a recent article in The New York Times (“Lessons in Longevity, from IBM”), Steve Lohr talks about the “post-monopoly prosperity” or how big IT corporations have to reinvent themselves when a dominant product is not anymore the engine of growth and revenue. More often than not, this reinvention process is triggered by a new company, which disrupts the business model of the incumbent. IBM underwent this “midlife crisis” in the eighties when Microsoft took the lead from IBM in the PC software industry. IBM was almost 70 year-old when it ended its “monopoly prosperity”.

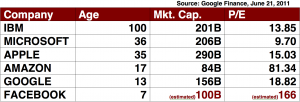

Nowadays, you do not have to wait to be 70 to experience a “midlife crisis”. Microsoft, with only 36 years is currently experiencing this challenge. Google Apps, a productivity software in the cloud for free or for only $50 per year in the enterprise version, is jeopardizing the $20 billion-a-year business of Microsoft’s Office. Microsoft has counterattacked by launching Office 365, a cheaper Office version in the cloud that is cannibalizing their biggest cash cow. In other words, Microsoft is forced to find alternative revenue sources to their traditional ones from corporations through the licensing of Windows and Office. Since, consumerization of IT is currently the force (see previous post) driving the IT industry, Microsoft is trying to enter in this ballpark with gaming and mobility but so far with mixed results. If we take a look to the P/E ratio (price-to-earnings ratio), which shows current investor demand for a company share, Microsoft decreased its P/E from 60 at the end of 2001 to a value of 10 this June. By contrast, the centennial IBM has a higher P/E of 14. In other words, investors remain to be convinced that Microsoft will be able to survive a “post-monopoly prosperity” phase.

If IBM and Microsoft are already in a “post-monopoly prosperity” phase: who is enjoying that privileged position? It is a shared podium, or at least it is what Eric Schmidt, Executive Chairman of Google, said in his interview at D9 All Things Digital Conference last May 31. Schmidt referred what he called the “Gang of Four” composed by Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook. According to Schmidt, in the past a single company was dominant in information technology, first was IBM and later was Microsoft. But now, the “Gang of Four” constitutes four consumer brands that provide something the user cannot do otherwise. All of them are using modern computer science in order to achieve aggressive scaling approaches. As a result, there are global companies and growing very fast in customers, reach and cashflow.

If IBM and Microsoft are already in a “post-monopoly prosperity” phase: who is enjoying that privileged position? It is a shared podium, or at least it is what Eric Schmidt, Executive Chairman of Google, said in his interview at D9 All Things Digital Conference last May 31. Schmidt referred what he called the “Gang of Four” composed by Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook. According to Schmidt, in the past a single company was dominant in information technology, first was IBM and later was Microsoft. But now, the “Gang of Four” constitutes four consumer brands that provide something the user cannot do otherwise. All of them are using modern computer science in order to achieve aggressive scaling approaches. As a result, there are global companies and growing very fast in customers, reach and cashflow.

However, there are major differences among the “Gang of Four” as shown in their P/E data. For instance, Apple has been around as long as Microsoft. However, Apple never enjoyed a monopoly position in the market, which forced Apple to reinvent itself several times: in 2001 with its entry in the music industry with the iPod/iTunes and later in 2007 in the mobile industry with the iPhone/AppStore. These two entries were received by investors as high earning growth opportunities, reaching a P/E of 281 in 2002 after the launch of the iPod and a P/E of 43 in 2008 after the launch of the iPhone.

Another interesting case is Amazon.com, which with only 17 years of operations and with a well-established e-commerce and logistics platform is adding a huge second revenue stream by positioning itself as one of the main cloud computing players. This entry is perceived with higher potential growth than its original core e-commerce business. This fact is reflected today with a P/E around 80, which normally is only assigned to start-up companies.

Notwithstanding, Google with only 13 years is currently in a crossroad. On one hand, it is creating a second revenue stream with Google Apps, which competes directly with Microsoft. On the other hand, their main revenue model based on search and advertising could be threatened in the near future by the social network Facebook, which exploits the identity business model associated to its more than 600 million users. Google is very aware that is lagging in social media. During the D9 interview, Schmidt even admitted, “I screwed up” regarding its social media strategy. For this reason and after the previous failures of Wave and Buzz, Google is trying again with a new social network called Google+ with an emphasis on privacy. However, it has to be seen if this new initiative will be this time effective against Facebook threat. Nevertheless, Facebook have not demonstrated yet that their $100B valuation in secondary markets (Facebook is not a public company) makes any sense. According to MSNBC, Facebook earned a profit of $600M in 2010, which translates in a P/E of 166.

Notwithstanding, Google with only 13 years is currently in a crossroad. On one hand, it is creating a second revenue stream with Google Apps, which competes directly with Microsoft. On the other hand, their main revenue model based on search and advertising could be threatened in the near future by the social network Facebook, which exploits the identity business model associated to its more than 600 million users. Google is very aware that is lagging in social media. During the D9 interview, Schmidt even admitted, “I screwed up” regarding its social media strategy. For this reason and after the previous failures of Wave and Buzz, Google is trying again with a new social network called Google+ with an emphasis on privacy. However, it has to be seen if this new initiative will be this time effective against Facebook threat. Nevertheless, Facebook have not demonstrated yet that their $100B valuation in secondary markets (Facebook is not a public company) makes any sense. According to MSNBC, Facebook earned a profit of $600M in 2010, which translates in a P/E of 166.

When is Google to undergo the same crisis Microsoft is experienced these years? It is difficult to give an exact date. However, it is clear that the speed of Internet time is also accelerating “midlife crisis” for these companies. IBM at 70, Microsoft at 35 and maybe Google at 18? It looks like the “half-life” or the period of time it takes for a leading IT company undergoing a “midlife crisis”. Obviously, there is no scientific proof for this “half-life” period, although the acceleration factor is caused mainly by Moore’s law. Let’s wait and see, but Facebook will probably experience its “midlife crisis” sooner than Google will experience it. After all, on Internet time, glory is not ephemeral. Ephemeral are only the companies that have it.