Carbon markets and the corresponding ES, often considered air regulation, are one of the longest-standing tools in the fight against climate change. Strong and sustained reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases would limit climate change and thus, mitigate the shocks that accompany it.

Given its condition as a transboundary issue, responses have normally come through international proposals. For instance, one of the paths has been the establishment of an international carbon market to put a price on carbon dioxide. The roots of this market date back to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, when countries joined an international treaty that later transformed into a regime, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Since then, this regime has explored ways through which the global rise in temperatures could be reversed. Fast forwarding a bit, in 2000, the Kyoto Protocol introduced the first carbon offsets. These offsets, named Certified Emission Reduction units (CERs), are tradeable units among nations equivalent to one ton of carbon and an instrument called the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) guarantees their exchange and integrity. The Kyoto Protocol established the first compliance international offsetting carbon market and set the precedent for a new wave of smaller-scale regional and national carbon markets.

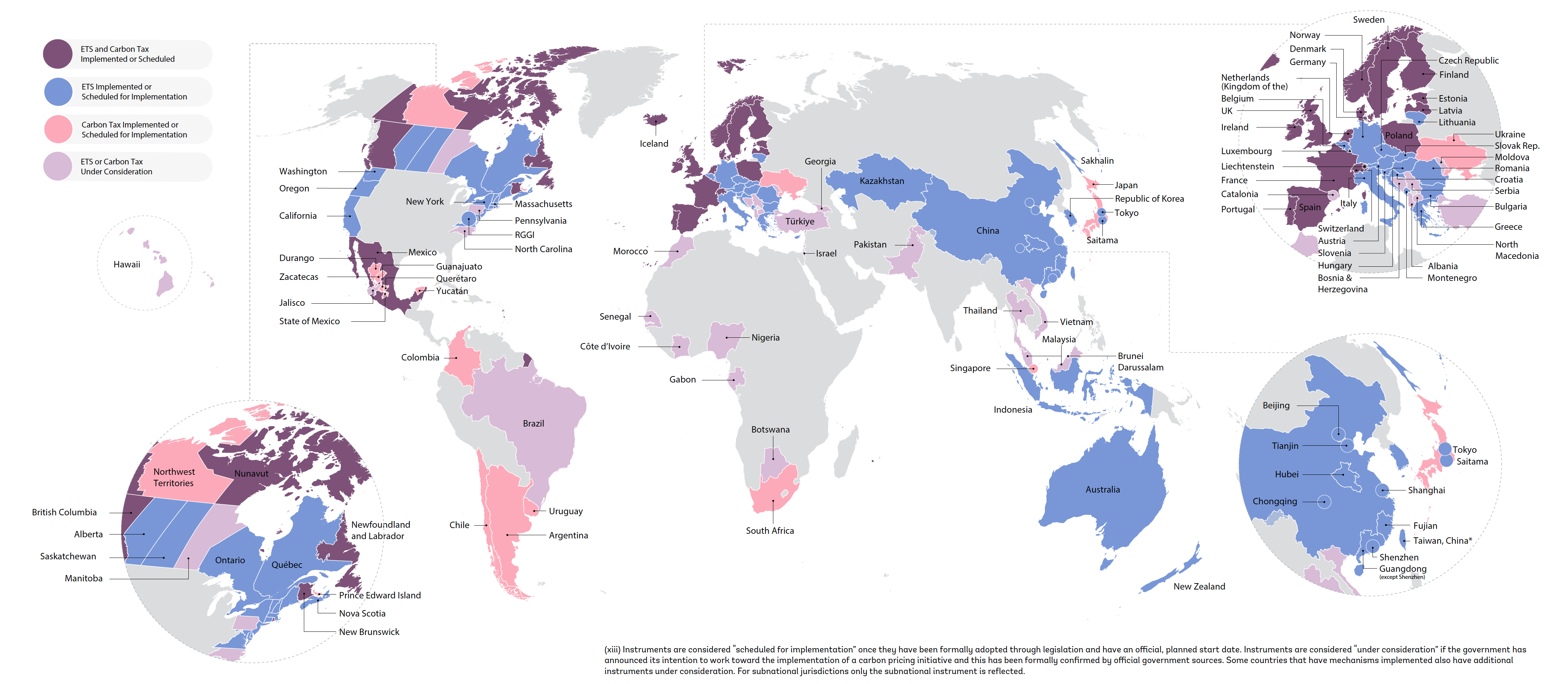

Initial ambitions quickly became unrealistic, making the commitments for the second phase of the Protocol, from 2013-2020, unachievable. The uneven decarbonization commitments between industrialized and developing countries made the second period of the Protocol unachievable and called for a renewed vision of global inclusion in emission reductions. This was finalized during COP 21, when the Paris Agreement was conceived and a global ambition goal of keeping the increase of global average temperature below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels and making efforts to limit at 1.5ºC. These targets have further accelerated the rate at which they resort to emission trading schemes (ETSs) or similar tools such as carbon taxes (CTs), as of April 2023 there are 73 in total.

Voluntary Carbon Markets

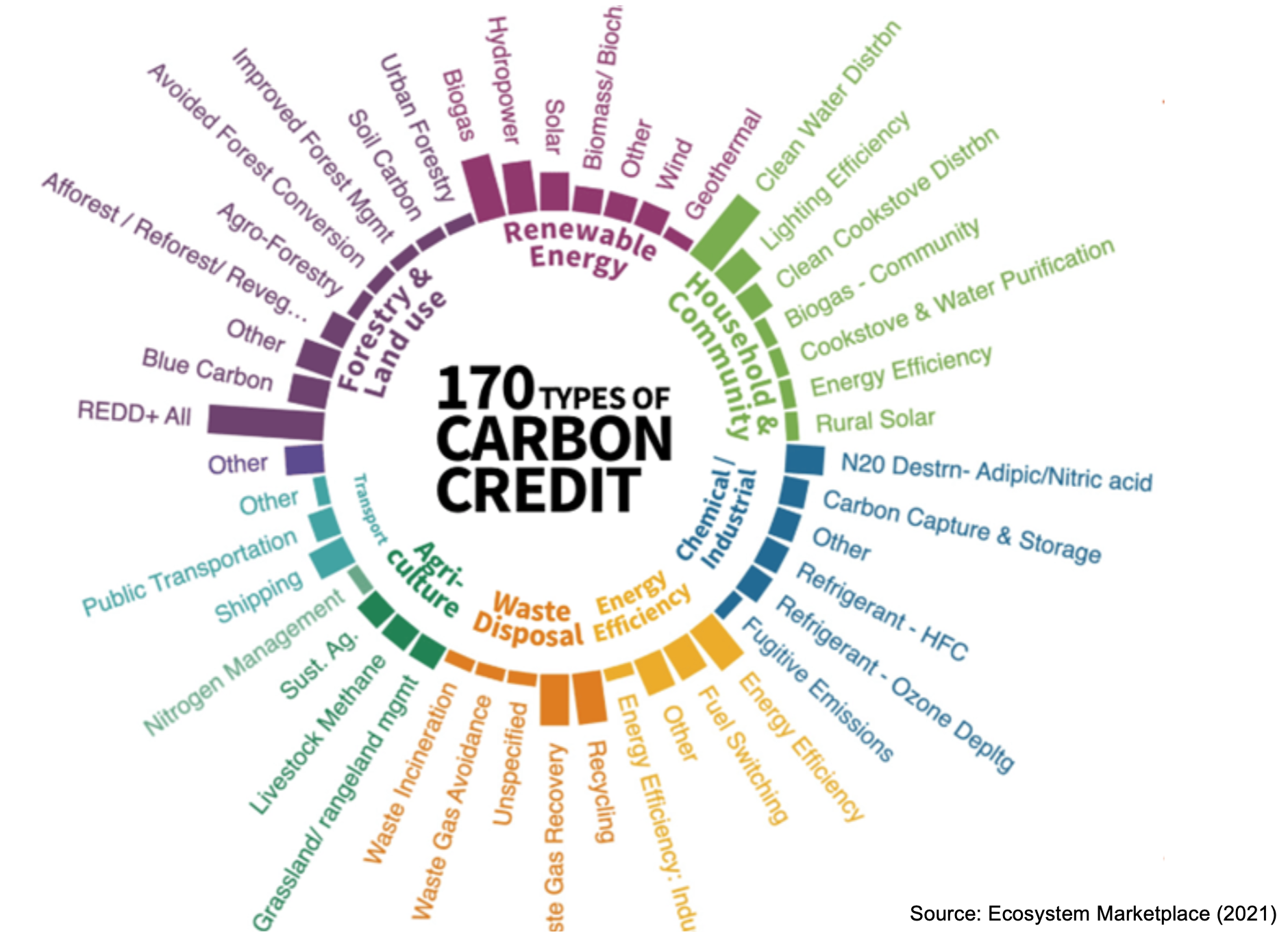

Beyond the compliance offsetting market, the Kyoto Protocol also set in motion a voluntary offsetting scheme for countries, companies and others willing to compensate for some or all of their emissions. The purposes that they have for doing so are variate, and are obviously correlated with the identity of the actor. To make a distinction from the offsets regulated under the CDM, credits in the Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM) are called Verified Emission Reduction units (VERs) as they are verified by external bodies not related to the UN and remain largely unregulated at present yet with potential to become the largest tool to counter climate change.

VERs fall into two main categories: they can aim to reduce or avoid emissions from current sources or they can be removal or sequestration credits that take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. The image below unfolds more thoroughly the abundant types of offsets.

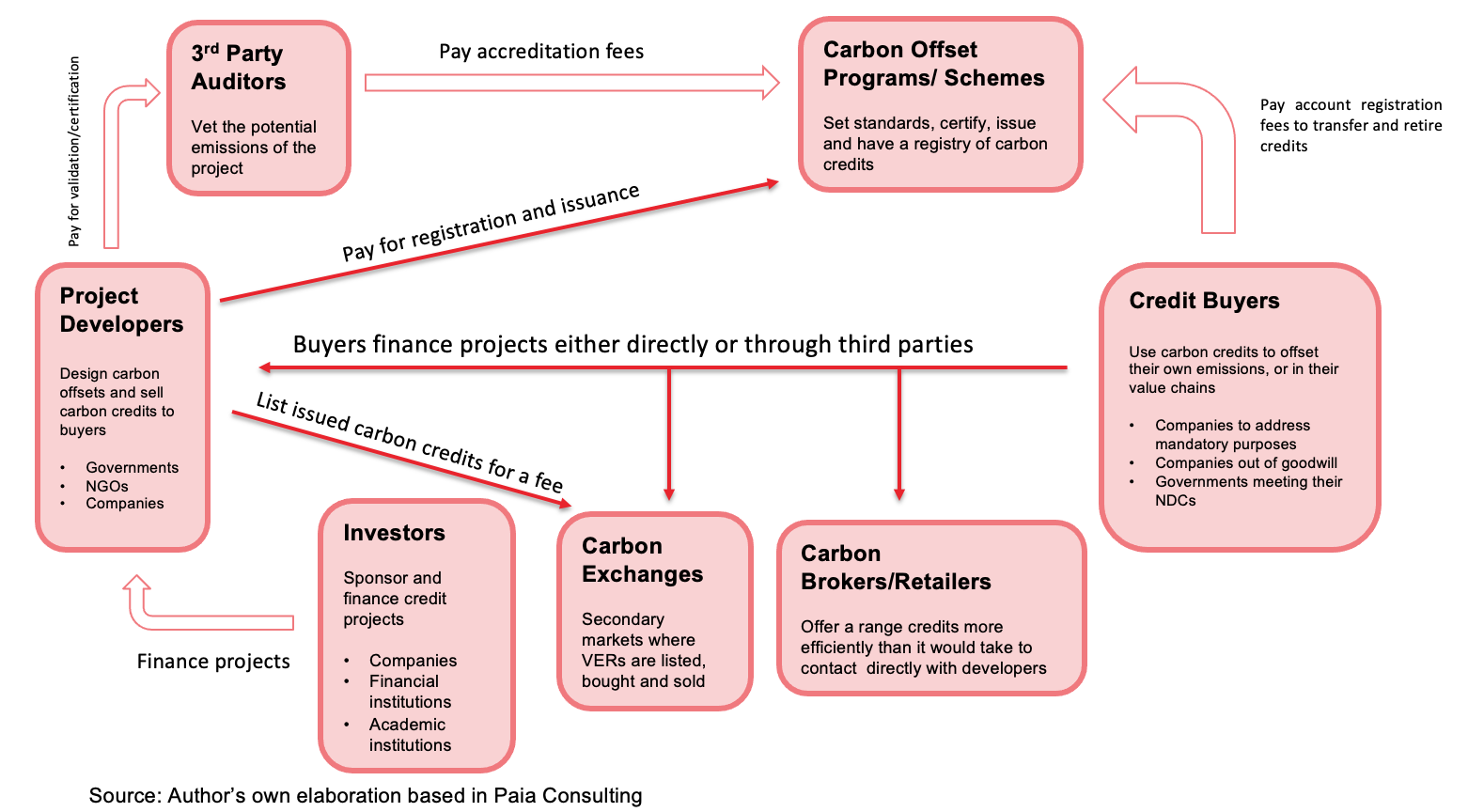

The urgency to deal with climate change have led to the creation of severely privately managed standards , with each having unique rules that all projects must follow in order to be certified. A central role is played by these standards, i.e. Verra and the Gold Standard. Besides these actors, the voluntary carbon credit ecosystem is composed of many other actors represented in the scheme below, strictly based in the works of Paia Consulting. The arrows represent the direction of the capital flow.

The image below provides a more visual representation of the layers of the VCM.