Warren Bennis, the management commentator, tell us that being able to articulate a vision in a way that is easily understood, desirable, and energizing, is the spark of leadership genius. If we want our message to have a long term effect on people, then it is the combination of the message and the flair and personal magnetism of the communicator that must inspire the listeners. When a charismatic speaker has successfully communicated an inspired message, social contagion does the rest. These two concepts are quite obviously related.

Warren Bennis, the management commentator, tell us that being able to articulate a vision in a way that is easily understood, desirable, and energizing, is the spark of leadership genius. If we want our message to have a long term effect on people, then it is the combination of the message and the flair and personal magnetism of the communicator that must inspire the listeners. When a charismatic speaker has successfully communicated an inspired message, social contagion does the rest. These two concepts are quite obviously related.

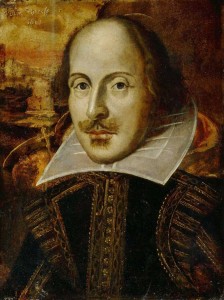

However, perhaps the difference between him and those ‘rock star’ CEOs which Collin’s speaks about is one of degree only and related more to personality type and communication style? Both want to achieve the same end but in different circumstances. In order to demonstrate the need for us to be politically astute in our communication, we have selected the flamboyant Julius Caesar as seen through the pen of William Shakespeare as our principal example. Shakespeare’s Caesar shows all the characteristics, both positively and negatively, of charismatic leadership in the extreme.

William Shakespeare, through fictional characters in a story context, touches on practically every aspect of human behavior. These, in turn, can easily be related to the behavior of people in the modern business corporation. We can find in reading these plays that they provide an opportunity for reflection on our own behavior, on that of their colleagues, and, more especially, on that of our own CEOs. Shakespeare, in fact, raises some very interesting human dilemmas through his fictional characters.

For example, in another of Shakespeare’s plays, Henry V, the ‘Agincourt’ speech is often seen as one of the great motivational speech in history but it is fictitious in that Shakespeare wrote it. It never happened. He used Henry historical position the ‘Hundred Years War’ to show how we can raise men’s sense of pride and honor against the greatest of odds through words and good delivery style. This speech is not primarily about history or kings and soldiers; it is about the power speech has to enact changes of attitude.

From a historical point of view,Englandwas emerging as a national state, and vision was important, just as vision is important for any business leader today. If we read and analyze the text of theAgincourtspeech, it can be a learning experience in the use of motivational language to sell a vision.

The bard in his historical plays and tragedies helps us to think about the choices available to us, the conduct of the people we work or associate with, and the impact of our own behavior on the world we live in. The bard invents clever and misguided strategies, struggles for leadership and power, prudent and imprudent decisions, and lies and deceptions. Although under vastly different circumstances, on reflection, many of these same struggles are similar in many ways to the politics of almost every contemporary organization. Let us go to play Julius Caesar, our main example.

Examining the life of Julius Caesar’s campaign in what is modern day France and Belgium, is not about the millions of people who died or were enslaved in his campaigns or about his the accumulation of wealth, but about how Shakespeare wants us to think about the pursuit of ambition. The assassination of Julius Caesar and the resultant confrontation between Brutus and Mark Anthony could be very instructive from the point of view of board room conspiracy over organizational reforms, for example. As the disagreement on the future governance ofRomecame to a head, heads began to roll. And a boardroom massacre resulted, in which Caesar was brutally removed. Shakespeare created this crisis situation of the greatest magnitude for us to ponder over.

Mark Anthony was one of Caesar’s most ardent supporters. But he was a dependent number two. He was a skilful player both in battle and in the political arena. His whole career was built round Caesar and he had everything to lose by Caesar’s departure. In fact, his career was basically over unless he took power himself. This was no secret, so what should Brutus have done? Should he, as the leader of the republican faction, have driven Mark Anthony away fromRomeimmediately after the assassination and not have given him the opportunity to fight back? Should he have followed the advice of Cassius and had Mark Anthony killed at the same time as Caesar was assassinated? Shakespeare portrays Brutus as a person who was acting for the best. But the bard asks us to contrast this with the thinking of the other conspirators. Did Brutus’ attitude make political sense? It was obvious that Mark Anthony would have to make a move, but why didn’t Brutus anticipate this? Was he so naive? We could, for example, ask ourselves here, had I been Brutus, what strategy should I have followed?

Even when Brutus refused to remove Mark Anthony, the gesture of his providing Mark Anthony with a public platform is intriguing. Why did Brutus allow Mark Anthony to speak on the steps of the Senate? Even after giving this permission, why did he allow Mark Anthony to have the last word? Surely he must have realized this was a dangerous step and that he, Brutus, should have the last word?

Then Shakespeare presents us with his two fictional speeches. Brutus starts his speech with a high level of credibility and respect from his Roman audience. He set out to use this credibility and his reason to persuade his audience of the righteousness of his actions. Shakespeare wants us to ask ourselves, “Can one rely on reason and a strong personal reputation in a crisis situation?” Can we afford to omit the use of emotion in such a situation? Was this a sensible strategy, in your opinion?

A noble appeal based on the speaker’s credibility demands respect, but if it does not arouse the right emotional appeal, it may not survive the onslaught of an emotional appeal by an opponent. We know that persuasion in a crisis situation has more to do with action and emotion than rationality. Reason, therefore, must be highly tempered with emotion to achieve the right action. Brutus’ speech fell widely off the mark. Mark Anthony’s speech, on the other hand, is one of the best examples of a crisis speech that one can find, because it rouses the right emotions in the audience while providing them with the hard evidence they need to be convinced. The result we all know, since the noble Brutus and Cassius were forced to flee as the Roman mob gradually turned against them.

But there are many other lessons to be learned from the bard in this play. For example, how should we deal with a conspiracy? Can co-conspirators cohabit after the event? Shakespeare poses this question. How seriously should Brutus have taken Mark Anthony’s known ability to seek revenge, especially considering Mark Anthony’s current position as Consul? Did Brutus have an alternative strategy? How did he plan in the circumstances to reinstitute a republican form of government based on the senate? Is there anything we can learn from Lepidus’s demise?

From Mark Anthony’s position, Shakespeare gives us many questions. Mark Anthony had to rule along with Caesar’s adopted son and heir, Octavius, and with Lepidus. We have the later struggle between Octavius and Mark Anthony to substitute Caesar after the Empire had been divided between them. If Mark Anthony had not have struck up his relationship with Cleopatra and returned toRome, would the outcome have been different? We have Octavius’ successful strategy to gain power. He confronted Mark Anthony and his new partner, Cleopatra, on their territory, and won, which eventually allowed him to establish himself as the new Emperor of Rome.

There are many other questions. Octavius declared Julius Caesar a god. This gave him the status of a god’s son. Octavius styled himself “Son of the divine Julius”. Later he went further and changed his name to the exalted name of Augustus.

In just one play Shakespeare gives us much to think about. In just one play, we have ideas that could affect our own positions in our organizations. We have examples of successful and, more especially, of unsuccessful strategies; we have uncontrolled ambition, we have lies and deception as well as their opposites. We have the example of an upright virtuous man failing because of his lack of practical wisdom. Are we aware of the reality that surrounds us in our companies?

Such plays raise fundamental questions which make us think about people’s behavior. We could ask ourselves why Brutus, who had a noble heart, didn’t succeed. Yes, Brutus was a virtuous man but he lacked one important virtue, prudence or practical wisdom. Can we point to a situation where there was a lack of practical wisdom in our action? Can we point to a situation where there was a lack of practical wisdom in either our manager’s or our colleagues’ behavior? How many times have we acted imprudently?

So how can Brutus’ naivety be related to middle manager behavior in modern corporations, you may ask? It has everything to do with it. Because corporations are where ambitious people gather in a competitive environment. By their very nature, they must be political. Brutus miscalculated people’s motivations and actions and ended up losing. Mark Anthony began by losing, then won, and finally ended in failure. Whether they succeeded or failed, it is interesting to know why. Maybe this is the best way for middle managers of learning how to deal prudently with boardroom politics without having to kneel at the altar of leadership gurus.

Reference

Collins, Jim. ‘Good to Great’, Random house Business, 2001

Shakespeare, William. ‘Julius Caesar’, Oxford paperbacks, 2008