In recent months, Japan – the world´s third largest economy – has returned to center stage. On April 4, Japan embarked on a daring economic experiment. After two decades of stagnant growth and deflation, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe presented a “three arrow” program:

- Monetary stimulus to end deflation – the Bank of Japan launched the largest monetary stimulus in history promising to double its monetary base and setting an inflation target of 2%.

- Fiscal spending to stimulate demand, followed by posterior fiscal consolidation

- Structural pro-growth changes.

After the announcement, GDP growth seemed to be picking up, the stock market boomed everywhere and risk premiums went down. Then, last week, the whole thing appeared to collapse, with the Nikkei plunging more than 7 percent in one day.

What is going on here? There are clearly several forces at work, but one is the role of the Money Multiplier.

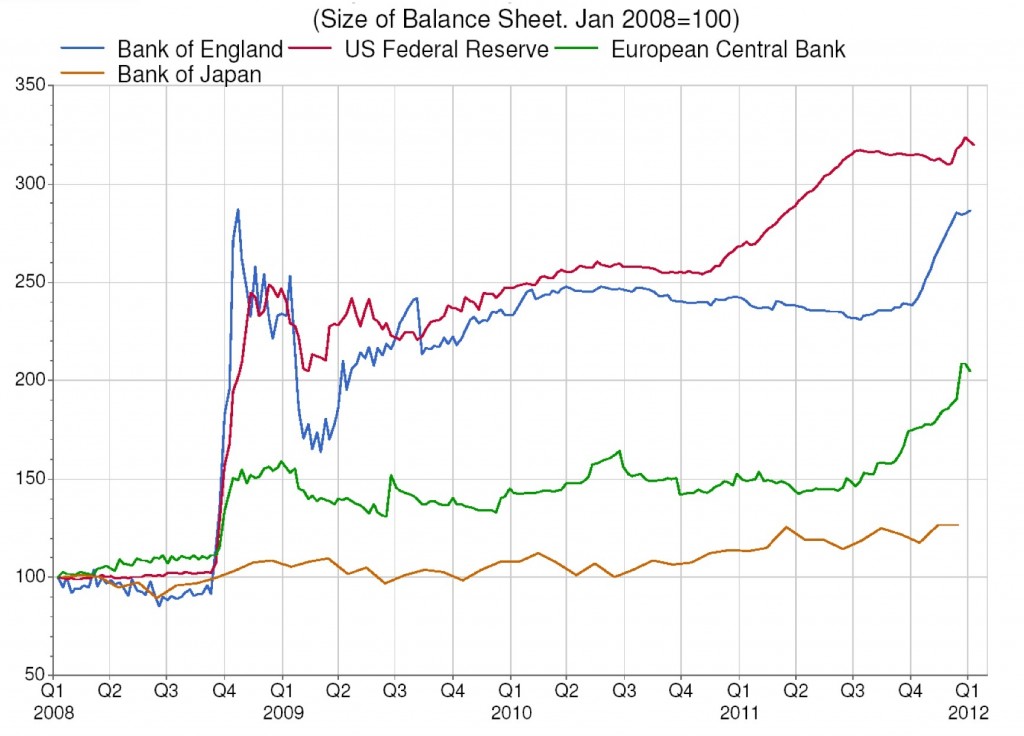

Japan has just been the last of the large economies to substantially expand its monetary base (see graph 1).

When a depositor goes to a bank to deposit her money, the bank lends a large proportion of the amount and keeps a small part in reserves. This loan can then be deposited again, contributing in this way to “create money.” Hence, once the money is printed by the central bank and thanks to the intermediation of financial institutions, the amount of cash in circulation usually ends up increasing by a certain proportion called the money multiplier.

In all these countries, if the money multipliers were functioning properly, there would have been a massive increase in cash that would have led inevitably to a significant rise in prices. And yet, none of these economies is experiencing much inflation. Why has this not been the case? In all of them, despite very low interest rates, firms and families are still saving and not spending, mostly due to severe damage on their balance sheets and on those of their banks after the recent bubble burst.

This is telling us that quantitative easing cannot increase inflation and stimulate the economy if the money multiplier does not work. That is, when families and firms cannot or do not want to borrow money and then spend it.

So will the bold “Abenomics” move work? It is still too early to say, but at least two additional elements are needed: first, structural reforms and second, a different view of the expectations and attitudes of the Japanese population.

“Japan has just been the last of the large economies to substantially expand its monetary base” is just wrong. Japan was the first economy to do it – and was heavily critizised. Afterwards, years later other economies followed.

I have read in some articles it could be a solution for the weak economies of South of Europe. Do you the same? Would the European Central Bank do the same movement to push these economies?