A key concept at the heart of financial theory is the “risk-free rate.” The idea is simple: the rate at which you would lend money to a very secure borrower, one with 0% probability of default. If you lend money to a riskier borrower (one with some probability of default) you would charge a “risk premium” or extra return due to the risk you bear (the probability of not being paid back). Like most successful academic theories, the idea is simple, clear and alluring; hence its widespread acceptance in the financial community. And yet, many would argue that you don’t need an academic to explain such a basic law of human behavior.

It becomes a problem when you try to apply that seemingly simple concept. It is certainly not a problem for academics, since they are not bound by the realm of practical application; their job is to develop theories. In any case, at some point either practitioners or academics (I’m not sure which) decided that the risk-free rate for a given currency is the rate of the treasury bond issued by the government of that country. For example, the risk-free rate of the Brazilian Real is the rate of the 10-year bond issued by the Government of Brazil; the same applies to the US Government with the dollar and the UK Government with the pound sterling. Each currency has its own risk-free rate. In the case of the EU, it is the German Bund that defines the risk-free rate for the euro.

In other words, the US Government, or any government, is considered risk free, with zero probability of default. Historically speaking, that assumption could make sense, since none of the major governments of the world have defaulted recently; nevertheless, there is historical evidence to the contrary. Consequently, most of the governments of large countries receive a credit rating of AAA, AA, or A, i.e., very high quality. So far, so good — everything sounds reasonable. But here are some facts.

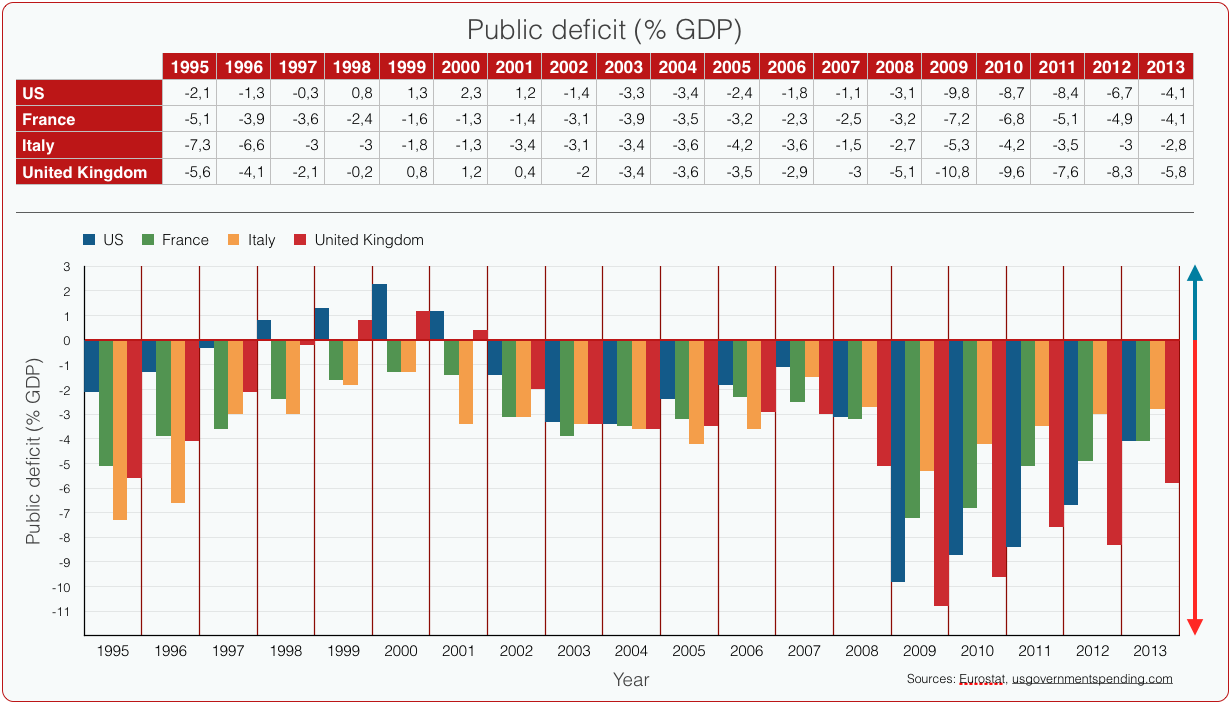

The first fact: Over the past 34 years (1980-2013), the US Government recorded losses (fiscal deficit) in 31 of those years ; in the case of the UK, 28 years; France and Italy never had a single year with fiscal surplus in all that time. A government having a fiscal deficit is exactly the same as a company losing money… the exact same thing. Governments are probably the only institutions in the economic world that consistently break the first basic rule of economics: “Make sure your costs don’t exceed your income.” Could you imagine a company recording losses in 31 out of 34 years?

OK, let’s assume we accept that governments record losses (fiscal deficit) every year. That brings us to the second fact: Could you imagine a company with 30 years of losses getting a rating of AAA from Standard & Poor’s , Moody’s or Fitch? Has anyone seen anything like that? I haven’t. So why do we simply accept that governments get such undue treatment? Well, it is part of the financial construction that we (well, they) have put together. Governments benefit from such favorable treatment, while markets make money lending to governments and in some cases even experience the power of having the governments at their mercy.

OK, for argument’s sake, let’s just say we accept that governments have perennial deficits and still earn AAA scores from credit rating agencies. Good for them. Theoretically that unfair practice would not harm me or my company. But here comes the third fact: Financial markets and their players assume that any company or individual poses a higher risk (greater probability of default) than the government. Thus, anyone borrowing will pay the government rate (the risk-free rate), plus a premium. Therefore, if the interest rate charged to the government goes up, so will the interest rate paid by any company or individual in the same country. In this case, I am taking a big hit as a result of the financiers’ theories and practices. Not only that, with this practice we are basing the entire financial system on a very shaky variable (the government rate) that could be manipulated by the markets or weakened by bad governments.

“With this practice we are basing the entire financial system on a very shaky variable (the government rate) that could be manipulated by the markets or weakened by bad governments”

If this is the case — and it is — a major financial player (or a group of them) could be tempted to drive up the risk-free rate of a country perceived as weak. With a higher interest rate, future loans would be more profitable for the investment bankers; the price of the government bonds would be lower, providing an opportunity to buy cheap and obtain future capital gains; the value of the companies in that country would be lower, giving an opportunity to acquire them on sale; and the same with real estate assets and in fact all assets present in the country. A huge profit opportunity for financial players.

At the same time, companies in that country would have less access to credit and at higher cost, leading to the collapse of some of them. This pattern of events has been ubiquitous in past crises. A clear sign of this is the growing level of profits of traders in times of high market volatility. Another sign is the proliferation of vulture funds buying up all types of assets at a discounted rate. In fact, the deeper the crisis, the worse the results for companies and individuals, and the better for the financial players . And it all started with an irrational application of the risk-free concept.

“This pattern of events has been ubiquitous in past crises. A clear sign of this is the growing level of profits of traders in times of high market volatility. Another sign is the proliferation of vulture funds buying up all types of assets at a discounted rate. In fact, the deeper the crisis, the worse the results for companies and individuals, and the better for the financial players. And it all started with an irrational application of the risk-free concept“

It is clear that in any country there is a multitude of people and companies that have better credit quality (or less probability of default) than their governments. It is clear that no one should be penalized for someone else’s bad behavior. And yet we as people and companies are penalized for others’ mistakes, whether those be governments or markets.

So, why do we have this ridiculous practice of assimilating everybody into the risk-free rate? I don’t know the answer to that question. I don’t know the intentions of the architects of this financial world. What we all know, however, is who profits from it.

“Despite the massive troubles caused by the recent financial crisis, no governments have done much to fix the markets. Only two explanations for this lack of action come to my mind: either the governments do not understand the markets or the financial players in the markets are too powerful”

Finally, how can we fix this mess? It’s simple:

- Do not tie everybody’s rating to that of their government. Rate everyone according to their financial health (or default probability, which is the same thing).

- Control the episodes of volatility in the debt markets (the ones that “decide” the risk-free rate). Have a true debt market (transparent, with many participants, none with a predominant position) and make it regulated (because there will be short periods when the market will not work).

To me, these solutions seem easy to put in place, with major benefits and very few and very minor cons (except for the financial players). It shocks me that, despite the massive troubles caused by the recent financial crisis, no governments have done much to fix the markets. Only two explanations for this lack of action come to my mind: either the governments do not understand the markets or the financial players in the markets are too powerful .

Great article! Thank you.

It is not only governments, but also central banks (with QE and such innovations in monetary policy) who can manipulate the so called risk free rate. Even to the extent of making it negative, which attacks the most basic common sense.