Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), a Roman citizen, was from Arpinum, south-east of Rome and, by some accounts, came to Rome as a boy to study at one of the city’s leading schools of rhetoric. Other commentators claim his primary education in Rome was under the tutorship of a private master.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), a Roman citizen, was from Arpinum, south-east of Rome and, by some accounts, came to Rome as a boy to study at one of the city’s leading schools of rhetoric. Other commentators claim his primary education in Rome was under the tutorship of a private master.

This meant that he was neither a patrician nor a plebeian(technically he would be classified in the plebeian category, according to James D. Williams, p.274) although in the Roman pecking-order he was an outsider. He owed his amazing rise to power to his brilliance as an orator in the law courts and the political arena. Indeed, he became one of the best known homines novi. In modern language, he would be classified as one of the aspiring classes. His family was reasonably well-off and had some social connections in Rome, which helped him greatly to integrate into Rome’s political and legal world. The name Cicero simply means ‘chickpea’ and although many colleagues urged him to change it, he stubbornly stuck to it, following the Roman tradition. The Roman name Fabius means beans, Lentulus means lentils and Catulus means a puppy. Indeed the name Caesar means bald, so he was in good company.

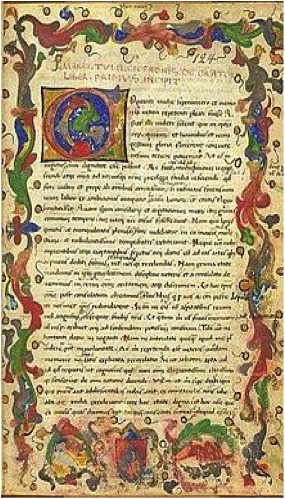

Cicero was sent to Rome for his schooling. At the age of fourteen, he was studying music, geometry, and the fundamentals of rhetoric. After his secondary studies, he went on to study literature, rhetoric, and philosophy under the tutorship of Lucius Linius Crassus. This opened the way for him some years later to study law under the famous Roman jurist, Quintus Mucius Scaevola. His studies were interrupted by two years in the military during the Social War, where he kept a low profile and he returned to his studies at the first opportunity. During the civil war between Marius and Sulla, he kept his head down and continued his studies in law and philosophy under the tutelage of Philo of Larissa, the head of Plato’s Academy, who had fled to Rome when Athens was invaded by Mithridates. It was with Philo that he learnt how to apply the techniques of rhetoric to philosophy, which is evidenced in his publications, Academica (45BC) and De Oratore (55BC). The De Oratore example (on the left) is 15th century edition found in Northern Italy and now at the British Museum.

Although there appears to be evidence of Cicero’s suffering from nerves and lacking in courage, this obviously did not prevent him from accepting difficult legal cases at an early age. One commentator on Cicero, Quintus Rufius Calenus wrote “why, you always come to the courts trembling, as if you were going to fight a gladiator, and after uttering a few words in a meek and a half-dead voice you take your departure, without having remembered a word of the speech … .” There may be some truth as to Cicero’s suffering from nerves, but few would accept his lack of courage. One of his first cases, taken at the age of twenty-six was that of Sextus Roscius where he mentioned the dictator Sulla (138BC – 78BC) and implicated his favorite, Chrysogonus. Indeed, he was lucky that Sulla didn’t have him killed.

A year after the Sextus Roscius case (80BC), Cicero conveniently left Rome for Athens on the advice of his friends to further his education in rhetoric. It was when he returned from Rome two years later (Sulla died in 78BC which opened the way for Cicero to return to Rome) that he entered the political arena. So, with friends in high places, enough money to spend on votes, and his greatly improved oratorical skills, he won his first election as Quaestor (Treasury magistrate) at the age of thirty-one. In this position he assisted the governor of Sicily and entered the curus honorum which facilitated him in the cultivated of new alliances such as that with Pompey. He was later elected Aedile (magistrate in charge of public buildings) and Praetor in 66BC. This left him in a good position to stand for the Consulship, and with the help of Pompey and other admirers this certainly was within his reach.

So at the age of forty-six, he successfully stood for the consulship against Lucius Catilina, which on one hand established him at the peak of his political ambitions, but on the other hand, laid the basis for his coming misfortunes. It was during his Consulship year that he discovered the Catiline conspiracy. Unfortunately he acted hastily and had the conspirators, one of whom was the step-father of Mark Antony executed without trial; an event that was to haunt him for the rest of his life.

In 58BC Publius Clodius Pulcher, who had become a Pleb purposely to run for the tribune, took out his revenge on Cicero by introducing a new law. The Leges Clodiae threatened to exile anyone who executed a Roman citizen without trial and to confiscate their property. Unfortunately Cicero, who had always relied on Pompey for protection, now found himself being turned away. Cicero had no option but to go into exile to save his life, and forfeit his properties.

When the Civil War (49-45BC) broke out between Pompey and Julius Caesar, Cicero sided with Pompey (even though Pompey had let him down) and joined his camp after Caesar’s victory at Pharsalus. This proved to be a fatal decision. Yet Cicero had luck in that Caesar pardoned him and allowed him to return to Rome. He lived uneasily in Rome, siding with the pro-Republican faction. Mark Antony, Caesar’s most trusted aid, resented Caesar’s protection of Cicero, but could do little while Caesar lived. The hostility between the two was so intense that Cicero had also tried to have Mark Anthony executed without trial early in the civil war. There was no way back; a struggle to death for one of them.

On Caesar’s assassination Cicero was once again at centre stage defending Republican ideals. But he showed a lack of public respect for Mark Anthony especially in the period immediately after Caesar’s death. His popularity was unrivalled as he tried to play off Mark Anthony against Octavian. The ploy backfired on Cicero when Anthony and Octavian joined forces in forming the Second Triumvirate with Lepidus.

Added to Mark Anthony’s resentment against Cicero was the fact that Cicero had given tacit support to the murder of Caesar. This, along with all the other issues, was a bad omen for Cicero when the proscription list was drawn up by the new Triumvirate. It surprised very few that Cicero’s name featured in it and that not even Octavian could get his name removed. Very shortly afterwards Cicero was hunted down and killed while trying to escape from Rome.

Reference: An Introduction to classical Rhetoric, edited by James D. Williams, Wiley-Blackwell (2009)