Why, a colleague asked me, should anyone be interested in a legal case that took place over two thousand and ninety years ago? My answer was simple. The case of Sextus Roscius shows how an efficient and successful use of pathos and ethos can turn a potentially hopeless case into one of triumph. Cicero’s client was acquitted of patricide by a Roman jury under the watchful eye of the political establishment. How did Cicero manage it, given the adverse situation? He managed to cultivate sympathy (pathos) for the accused, by associating Sextus with ancient Roman rural values and positing them against greedy amoral city ways; and by undermining the credibility (ethos) of those who instructed the prosecution.

Why, a colleague asked me, should anyone be interested in a legal case that took place over two thousand and ninety years ago? My answer was simple. The case of Sextus Roscius shows how an efficient and successful use of pathos and ethos can turn a potentially hopeless case into one of triumph. Cicero’s client was acquitted of patricide by a Roman jury under the watchful eye of the political establishment. How did Cicero manage it, given the adverse situation? He managed to cultivate sympathy (pathos) for the accused, by associating Sextus with ancient Roman rural values and positing them against greedy amoral city ways; and by undermining the credibility (ethos) of those who instructed the prosecution.

Background to the case

Although many of the facts of the case are unknown, we do have Cicero’s final draft to help us stitch together an outline of the background. Sextus Roscius, a wealthy landowner from Ameria, was murdered in Rome in 81BC. He had lived in Rome while his eldest son, also called Sextus Roscius, ran the family estates in Ameria. There seemed to have been very poor relations between Sextus Roscius senior and his son over the possible inheritance of the estates. But Sextus senior also had difficulties of communication with his immediate relations, Magnus and Cipito Ruscius, over the ownership of some of the property.

Both Magnus and Cipito teamed up with Chysogonus, a high profile ex-slave and close friend of Sulla, the dictator, to secure possession of Sextus senior’s estates in Ameria. Chysogonus had Sextus’ name added to the proscription list, and in this way Sextus could be killed and his property would automatically pass over to the state. The state would then make the property avaiable to Chysogonus and his two accomplices at a very good price. In this particular case the entire property was worth six million sesterces and was sold to Lucius Cornelius Chrysogonus for the very trifling sum of two thousand sesterces. On seeing Sextus junior being removed from the estates, a group of good-minded citizens of Ameria appealed to Sulla directly to have Sextus’ name taken off the proscribed list and for Sextus junior to inhertit his father’s estates. But Chysogonus, on meeting the delegation on behalf of Sulla, did not reveal his personal interest, and saw to it that the petition never bore fruit. However, as the proscription list had been closed a year before the murder took place, the sale of the estates appeared to have been premature. So an alternative strategy had to be found as to what to do with Sextus’ son.

Surely Sextus junior was entitled to inherit the property, now that his father’s name had been or was about to be removed from the list? Surely it was imperative that he be removed permanently. So the conspirators found a compliant advocate, Gaius Iulias Erucius, to file an accusation of patricide against Sextus junior in the courts. If found guilty, Sextus junior would face a painful death and Chrysogonus’ problem would be solved.

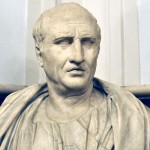

Sextus junior, on hearing this, fled to Rome and put himself under the protection of Caecila Metella Balearica Major, known as Caecila, the priestess. Caecila had been a close friend of Sextus senior and was part of the powerful Metelli family. Many lawyers were approached to defend Sextus junior, including the famous Hortensius, but they all refused, obviously being afraid of Sulla’s wrath (not forgetting the close relationship which Sulla had with Chryosgonus). It was Caecila who recommended the twenty-six year old Cicero, who accepted the challenge. He showed courage in taking on the case, knowing that the dictator would take a very dim view of those who opposed him or his inner circle.

The Case: An appeal by way of Pathos and Ethos

Cicero claimed at the beginning of the case that the charge was baseless. According to W. B. Sedgwick, the dilemma which Cicero in his defense presented was as follows: “If Roscius I (the father) was proscribed, Roscius II (the son) could not be prosecuted for his murder; if he was not proscribed, the property was illegally sold.” Sedgwick claimed in his 1934 article in The Classical Review that Cicero avoided addressing this dilemma because Chrysogonus had already removed Roscius I’s (the father’s) name from the proscription list. Sedgwick says that when the delegation of men from Ameria came to Sulla’s camp, Chrysogonus had persuaded them to leave without seeing Sulla, by promising to set everything right himself and by taking Roscius I’s name off the proscription lists as an act of good faith towards the delegation. This act on Chrysogonus’ part necessitated the charge brought against Roscius II in order to clear the former as well as the Roscii of all wrongdoing. Also, Sedgwick claims that with Roscius II removed, “no questions would be asked.”

Creating credibility through ‘identification’

Cicero had a difficult job on hand in that a jury was unlikely to go against one of Sulla’s favourites. Sextus’s defense called for something special. Cicero decided on exploiting ‘Identification with the ancient values of Rome’ as one of the pillars of his defense. This invariably meant positing the virtues of country life, such as hard work and honesty, against the vice and corruption of urban life. These rural people are trustworthy and this is why his father entrusted him with the running of the estates. If this trust had not existed, Sextus senior would never have left the land to his son to manage.

Cicero, with very little hard evidence decided on a defense based on Pathos and Ethos. His opening speech paraded the virtues of the hard-working farmer, who was the very foundation of the glorious city of Rome. Cicero fails to produce much evidence (which in any case he didn’t have), but denies the assumption that the father relegated his son to the farm because the younger Roscius had incurred too much debt. By identifying his client with solid rural values and his prosecutors with the urban ones, Cicero was able create a stereotype in the minds of the jury. The idea of the virtuous farmer and vice-ridden city dweller serves as a wholesale substitute for the lack of facts. He managed to associate the prosecution with greedy amoral city types.

Most of Roman audiences at that time would have assumed that a father who did not particularly like his eldest son would give him the management of the estate, which they would view as slave work. It was more a punishment than a reward to live outside Rome. Cicero counteracted this view by painting the virtues of the farm in terms of the ancient virtues that built Rome. Cicero cleverly spoke in a way that showed that the elder Roscius was not only fond of his son but trusted him entirely to the extent that he entrusted him with the responsibility of managing the estate for the family. How did Cicero turn the prosectution’s argument to his favour?

The metaphor as a rhetorical tool

In doing this, Cicero used a metaphor very effectively. He introduced the comic and popular play, ‘Hypobolimaeus’ as a means of comparison with his client’s circumstances. The play was about a father and two sons, exactly like the present case, where one son stayed on the farm, not as a punishment, while the father and the second son lived in Rome. He compared the two situations. In the present case Sextus senior and his youngest son Gaius had gone to live in Rome, leaving Sextus junior to manage the estate. The father, he claimed, absolutely trusted his son’s management abilities. The comparison worked. Cicero was able to show that the charges were baseless and that his client lacked any motive to kill his father.

Cicero then moved on to accuse Magnus and Cipito of the murder, and successfully shifted the spotlight from his client to them. He produced evidence that Magnus was in Rome the night of the murder, and of his return to Ameria immediately after the murder, bringing the stained dagger as proof. He then successfully linked this with corruption, and how Magnus, Cipito and especially Chrysogonus were to gain from the whole sordid affair. The case showed courage on the part of Cicero, as Chrysogonus with his close connections to the dictator Sulla could make life quite dangerous for anyone who stood against his interests.