Following up on the topic of extreme cases of expatriation that I recently touched upon, today I would like to review an interesting piece of academic work. Specifically, the scholars Fisher and Hutchings (2013) examined the relationship between cultural distance (CD) and expatriate adjustment in a rarely addressed area of intercultural collaboration in the military context. In general, the study results significantly enrich current knowledge of expatriate adjustment, as they revealed that an extreme context has a critical influence on the relationship between cultural distance and adjustment.

Following up on the topic of extreme cases of expatriation that I recently touched upon, today I would like to review an interesting piece of academic work. Specifically, the scholars Fisher and Hutchings (2013) examined the relationship between cultural distance (CD) and expatriate adjustment in a rarely addressed area of intercultural collaboration in the military context. In general, the study results significantly enrich current knowledge of expatriate adjustment, as they revealed that an extreme context has a critical influence on the relationship between cultural distance and adjustment.

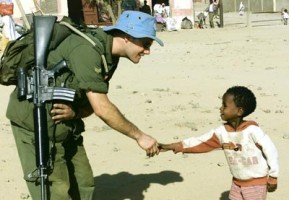

When speaking about intercultural collaborations, one of the key roles attributed to expatriates relates to facilitating such collaboration through their boundary spanning. As my own research suggests, this role is quite critical, and it requires building social ties and interpersonal trust for the purposes of knowledge sharing between the two different entities. Given the intercultural context of such collaborations, the adjustment to cultural differences between the parties becomes vital. Indeed, poor intercultural interactions may lead to early repatriation, damaged relations between the parties, and unsatisfactory assignment results. And what if we talk about intercultural collaboration in an extreme military context? Naturally, all challenges are further amplified. As the study authors note, in an extreme environment poor intercultural communication, misunderstandings, or interpersonal conflicts, may result in injuries or even cases of death.

Study findings

Examining the historical case study of Australian military advisors during the Vietnam War, the researchers wanted to find out which attributes of cultural distance matter the most to military expatriates and their adjustment process. A total analysis of 33 interviews and additional assessments of many archived documents revealed that military expatriates were mostly concerned with differences in terms of profession (e.g. aptitude of soldiers), ethics (e.g. adherence to laws), culture (e.g. lifestyle differences), language, social and political milieu (e.g. local ‘taboo’), as well as communication style (e.g. showing emotions in public).

Certainly all these aspects can also challenge adjustment during an ordinary business assignment. However, the study authors highlight that context matters, making a clear distinction between mundane, crisis and extreme contexts. In mundane contexts, expatriates have access to different resources that would help their adjustment, and there is rarely an urge for immediate adjustment, because failure would not entail life-threatening results. Crisis is a short-lived phenomenon, which also reduces the importance of experiencing cultural differences. By contrast, dire circumstances of extreme contexts make the interpretation of cultural differences much more acute, and hence may have much more serious implications. In addition to the influence of psychological stress on one’s ability to analyze, make decisions and control behavior, other factors accentuate cultural differences in an extreme environment. Unlike mundane assignments, during extreme assignments there is not much separation between work and non-work time. For example, a business assignee may forget the burden of (work) adjustment as soon as the working hours are over and he or she walks out of the office. In contrast, military expats do not usually have fixed working hours, and the extreme context in their work is ever present.

Practical implications

In general, the study highlights that cultural distance has far-reaching and possibly deadly consequences in extreme military contexts.

As such, cross-cultural training is a necessary and critical aid for preventing negative consequences. Specifically, organizations are advised to get a thorough knowledge of potentially harmful cultural differences, such as local customs and political views of the population. Although not explicitly mentioned in the reviewed study, I would argue that there are also implications for cross-cultural training of the receiving part. Such an approach would be in line with previous research on knowledge sharing, which demonstrates that intercultural collaboration depends not only on expatriates’ willingness and ability for knowledge transfer, but also on host-country nationals’ willingness and ability to receive this knowledge.

Finally, expatriates in extreme contexts are likely to encounter plenty of ambiguous situations, which require immediate decisions. Therefore, the study highlights the importance of professional ethos or guidelines that would help to make decisions in critical situations.

Further reading:

Fisher, K., & Hutchings, K. (2013). Making sense of cultural distance for military expatriates operating in an extreme context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 6, 791-812.