Cross-cultural psychologysuggests that we may experience difficulties in cross-cultural interactions due to differences in communication styles. For instance, one of these differences concerns the communication context. Specifically, countries like England, US, and Germany are considered to be low-context cultures, in which information is conveyed directly and explicitly, and which rely heavily on verbal communication. In contrast, Asian, African and South European cultures are considered to be high-context, which means that communication is rather indirect and seemingly ambiguous, with a lot of emphasis put on non-verbal language and contextual cues. In other words, in high-context cultures you need to read between the lines. Given that the differences in communication context are relative – thus, even an American employee going to Germany may experience these differences – ‘reading between the lines’ or understanding the context becomes an essential skill for globally mobile employees and culturally diverse teams.

Cross-cultural psychologysuggests that we may experience difficulties in cross-cultural interactions due to differences in communication styles. For instance, one of these differences concerns the communication context. Specifically, countries like England, US, and Germany are considered to be low-context cultures, in which information is conveyed directly and explicitly, and which rely heavily on verbal communication. In contrast, Asian, African and South European cultures are considered to be high-context, which means that communication is rather indirect and seemingly ambiguous, with a lot of emphasis put on non-verbal language and contextual cues. In other words, in high-context cultures you need to read between the lines. Given that the differences in communication context are relative – thus, even an American employee going to Germany may experience these differences – ‘reading between the lines’ or understanding the context becomes an essential skill for globally mobile employees and culturally diverse teams.

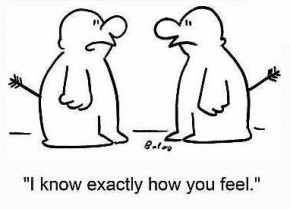

But why do we need to understand the context? Mainly because context adds meaning to verbal messages. For instance, emotions, which are more likely to be transferred by means of voice tone, body language and facial expressions, are an important part of every message. In fact, one reason for why we tend to use emoticons while electronically messaging is to reduce the risk of misunderstandings. Highlighting the importance of attending to emotions in cross-cultural settings, one of my previous blog posts argues that empathy, i.e. understanding and relating to the feelings of others, is a crucial part of cross-cultural communication and a required skills for global leaders.

Empathy: some fascinating evidence

The topic receives further impetus based on the results of relevant research led by Antonio Damasio from University of Southern California’s Brain and Creativity Institute. Specifically, this fascinating research (2009) suggests that emotions related to our moral sense, such as empathy, awaken slowly and take time to develop.

Using real life narratives to evoke different emotions, including the ones related to other people’s physical and psychological pain, researchers examined the brain functioning of study volunteers. In essence, participants were asked to listen to the stories and were then put into an MRI scanner to examine their brain functions. The results indicated that emotions pertaining to psychological and physical pain engaged different neural systems, meaning that we use different brain cortex areas for responding to different types of pain. As Damasio puts it, ‘The brain is honoring a distinction between things that have to do with physicality and things that have to do with the mind’.

What is even more important is that due to the different neural systems used, it takes us longer to process and respond to others’ psychological pain than to their physical pain. Specifically, people are capable to respond to others’ physical pain within fractions of seconds, while responding to psychological pain took an average of six to eight seconds. As such, the more sophisticated mental process of empathizing with psychological suffering unfolds much more slowly than empathizing with physical suffering.

Why would that matter in the context of global leadership?

Even though empathy is important in any leadership context, it becomes particularly thought after in multicultural settings. As already highlighted, empathy is a needed skill for global leaders, as it helps to communicate with and understand culturally diverse employees.

The discussed research suggests that empathy does actually take time, and the more distracted or mentally overloaded we are, the less we are able to experience the subtlest, most distinctively human emotions such as empathy and compassion. In other words, if things happen too fast, we may not fully experience and acknowledge emotions about other people’s psychological states. Now, a multicultural environment is exactly a place where things tend to unfold very fast.

Operating across cultures means operating under conditions of increased complexity, as reflected by the existence of multiple and often interrelated stakeholders, high levels of ambiguity and the need to deal with different rates of change across contexts. It also means more frequent use of virtual forms of communication (e.g. virtual teams) and less face-to-face contact, which implies possible cross-cultural difficulties and misunderstandings. As a result, there is often less time for sufficient emotional attachment and hence potentially less space for conveying empathy towards cultural others.

All in all, the discussed research adds to our knowledge, suggesting that in cross-cultural settings the capability to empathize with culturally different others is not only a matter of cultural intelligence, attention to non-verbal language and context, but also a matter of time. Empathy takes time, and this is something global leaders need to account for.

Excellent post, Sebastian! After having the opportunity lo live in several countries I’ve come to realize that help is not always helpful. One thing is to notice others’ pain and/or suffering, other thing is to take actions to increase others’ wellbeing. In both stages of the compassionate action, cultural relativity may affect the effectiveness of helping behavior, even if the intension is to help. We need to increase our awareness regarding how to provide help because even if we indeed help alleviate one problem, we may even creating another.

To a very large extent i agree with your article but the context is being globalized by the effects of globalization so in the end interactions are becoming more homogenous across the world. i think a more disruptive factor is religion

sebastian thanks for sharing useful knowledge for us , I will bookmark this page first, then I read.