After the landmark agreement between China and the United States back in November, I wrote a post which quoted Sunita Narain, from India’s Centre of Science and Environment, who has eloquently argued that if both China an the US emit 12-14 tons of CO2 per person per year then the rest of the world will not be able to emit very much at all!

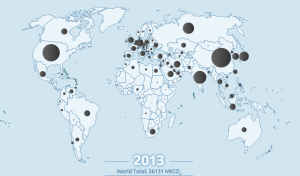

India is currently the world’s third largest emitter of CO2 but its emissions are half of the United States’ and a quarter of China’s. Looking at the issue on a per capita basis India is at 1.9 tons of CO2 per person per year compared to 16 for the U.S. and 7.9 for China today!

Approximately 300 million Indians lack access to electricity and in much of the country supplies are intermittent and unreliable. Despite the fact that India’s prime Minister, Narendra Modi has committed to bringing 100 GW of solar power on line by 2012, most analysts believe that coal, which India has in abundance, is the country’s best bet for electrification and continued economic development.

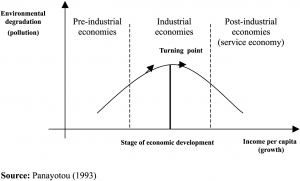

Environmental Kuznets Curve

Writing about inequality and wealth, economist Simon Kuznets found that the relationship had an upside down U shape and that both poor societies and rich societies were more equal than societies in the middle where inequality was higher. In the 1990s a number of researchers such as Grossman and Krueger (1991) and Panayotou (1993) found a similar pattern in the relationship between economic wealth and environmental performance and this is often called an environmental Kuznets curve.

Poor countries produce little environmental damage as their lives tend to be closer to nature and use little energy. As a country gets richer its people tend to use more energy and produce more CO2 and other pollutants. This process continues until the environmental costs becomes significant and wealthier people are able to focus more on their surroundings, implement political controls and adopt cleaner technologies. While the idea is simple in theory and holds true in many applications, the details are different in different places and for different measures of environmental sustainability such as air and water pollution, carbon emissions, etc.

India is an interesting example as it had made important advances in air pollution even though its income levels are normally below the threshold beyond which one would expect things to improve. Water pollution continues to be a problem although Prime Minister Narenda Modi has launched a new effort to save the ganges as discussed in another post back in October.

Et tu Greenpeace?

Perhaps the most interesting twist to the story in India are reports that the Modi government is restricting the travel and finances of western environmental groups active in the country such as Greenpeace, 360.org and The Sierra Club. Reporting for the Los Angeles Times, Shashank Bengali Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, saying that environmentalists who are against India burning coal are “acting as foreign propagandists and foreign agents.”

Meanwhile the Modi government is working hard to make it easier for foreign firms to do business in India and potentially will create a booming market for energy, water, and other needed infrastructure.

Prof: If I may say a few words about the story from India. There’s a lot more nuance here that may not be apparent internationally.

Frankly, it was shocking to see that Greenpeace activist, Priya Pillai, being offloaded from a plane to London to stop her from doing a deposition in front of the House of Commons; it’s a flagrant violation of the spirit of the Constitution, if not in letter. Not the first time the Indian government has pulled shenanigans of this nature; don’t want to discuss this in a public forum, but I personally know quite a few international journalists who were denied visas to travel to India to meet their families: completely shocking and unacceptable coming from the world’s largest democracy. The government has had a secret witch-hunt of sorts; they like to maintain an image of international acceptability, but are quite ruthless and vicious when it comes to individuals or groups. A bit like Turkey’s Erdoğan in that regard; being business-friendly, but ruthlessly chasing down activists and journalists, while at the same time, encouraging revisionist history about the country.

Crucially though, think we can objectively say the Modi government is *not* one for environmentalism. For instance, while they publicly have a “Swacch Bharat Abhiyaan” (“Clean India Campaign”), in reality, they have built only half the number of toilets as compared to the previous government for the same period.

Which, frankly, doesn’t leave much room for optimism about cleaning up Ma Ganga; it has about half a million times more faecal coliform bacteria that India’s permissible limits. It’s also one of the world’s longest rivers; the FT piece I linked to suggests that we won’t see it clean in our lifetimes even if the PM starts something now (which, as I had alluded to, is in itself a big question mark)

Likewise, despite public pronouncements, they have actually chipped away on a lot of existing environmental protection; not only have they removed the moratorium on building new factories in India’s most polluted areas, they have also tried to substitute a regulatory framework with self-regulation. They also seem to be tweaking an index that measures industrial pollution.

They have also done away with public hearings for new coal-mines, and drastically weakened protection for wildlife reserves.

In fact, wildlife protection is an interesting insight into Prime Minister Modi. In his earlier tenure as Chief Minister had steadfastly refused to implement the Supreme Court’s directive to shift a portion of lions from his home state Gujarat to a second sanctuary, to protect the species from epidemics that could wipe them out; that order has remained unimplemented for the last 10 years, despite repeated rulings by India’s highest court.

If I were to read character traits into this, I’d venture that PM Modi has had a history of being stubborn and emotional about certain policy questions, which is great when it comes to certain economic reform or nationalistic policies; it is, however, not a trait that’s conducive to rational, environment-friendly, arguments. Perhaps India won’t be the country that will buck the Kuznets curve, after all.

The post above from a former student adds an enormous amount of context to the discussion and calls into question the commitment of Prime Minister Modi to cleaning up the Ganges, protecting Indian wildlife, etc. It also shows that the local situation is always more complex and nuanced than what is reported in the national media!