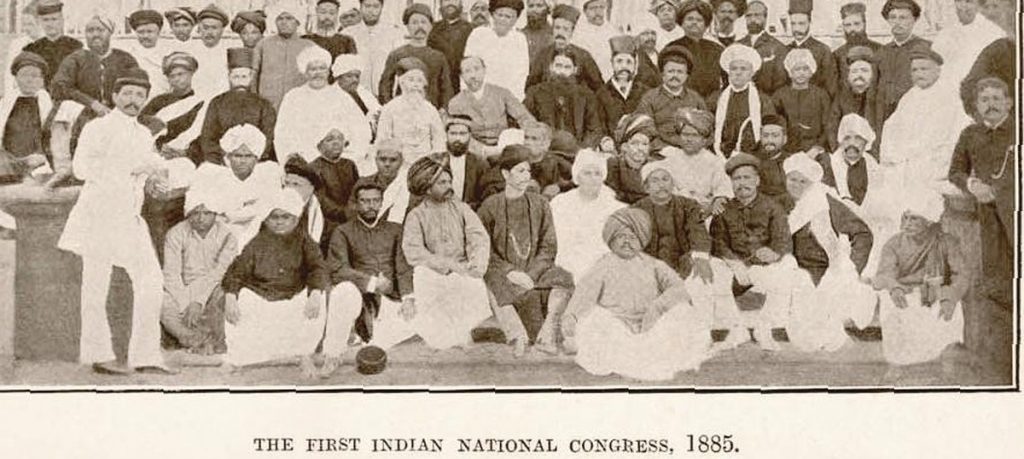

According to John Keay’s excellent history of India, the process leading up to the partition of the subcontinent and the independence of India and Pakistan played out over many years and could be said to have begun in the 1880s. The British Viceroy from 1880-1884, Lord Ripon, was a liberal who began to encourage rather mild reform which would allow more native Indians to serve in the civil service. When Ripon was recalled in 1884 educated Indian elites rose up in his defense and according to Keay, this was the spark that created the first Indian National Congress in 1885 which was initially led by a Scot who had served in the Indian government, Allan Hume.

According to John Keay’s excellent history of India, the process leading up to the partition of the subcontinent and the independence of India and Pakistan played out over many years and could be said to have begun in the 1880s. The British Viceroy from 1880-1884, Lord Ripon, was a liberal who began to encourage rather mild reform which would allow more native Indians to serve in the civil service. When Ripon was recalled in 1884 educated Indian elites rose up in his defense and according to Keay, this was the spark that created the first Indian National Congress in 1885 which was initially led by a Scot who had served in the Indian government, Allan Hume.

Working within the system

Over the next 34 years, the movement for increased involvement of Indians in the government grew to include the call for home rule, which essentially meant that India should become like Canada or Australia as an independent part of the British empire. The actually story is much more complex with different currents corresponding to regional issues across the varied parts of the region, coming together and drawing apart of the Muslim and Hindu leaders and also disagreements about style and tactics. There was for example a group of so called Ghadrite activists who openly called for mutiny against English rule as well as the more peacefully focused followers of Ghandi who focused on specific issues such as the plight of Indigo workers in Bihar or farmers in Gujarat.

According to Keay, with the exceptions of the Ghadrites, the majority of Indian politicians and activists were educated in the english system or even in England itself, were largely loyal to the crown, and committed to the idea of home rule under the guidance and support of the English.

Over one million Indians fought for England during World War I and while it was going on the Defense of India Act was passed curtailing civil liberties and allowing the government to jail and execute suspected Ghadrites. In 1919, a new Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, appeared to support the idea of eventual home rule but also put through legislation to retain the police powers in a series of laws essentially allowing the government to jail suspected activists without charges, trial, or possible appeal. In protest of the new laws, a national protest was called which resulted in a riot in the Sikh holy city of Amritsar in which five europeans were killed.

Too much to forgive

In order to establish order, a British General, Reginald Dyer, occupied the city and on the 13th of April took his troops to break up an assembly at a place called the Jallianwala Bagh. Dyer had his men block the entrance and immediately ordered them to open fire killing between 379-500 people and wounding another 1,200 men women and children who were most likely there to celebrate a feast day which had nothing to do with politics.

After the horror of Amritsar, the call for home rule was abandoned and Indian politicians and activists of all kinds, including Motihlal Nehru, came together to call for full independence and for the English to simply leave. It would take almost twenty years and another World War for the process to finally come to fruition but a critical message is that in many ways, the nature and goals of the independence movement were shaped as a reaction to the British policy and actions taken by individuals such as General Dyer who was never punished for his crime in Amritsar.

After the horror of Amritsar, the call for home rule was abandoned and Indian politicians and activists of all kinds, including Motihlal Nehru, came together to call for full independence and for the English to simply leave. It would take almost twenty years and another World War for the process to finally come to fruition but a critical message is that in many ways, the nature and goals of the independence movement were shaped as a reaction to the British policy and actions taken by individuals such as General Dyer who was never punished for his crime in Amritsar.

Let’s hope the politicians involved in the myriad crisis around the world have the time to read history and avoid its mistakes.

Dear Prof. Rosenberg,

The Spanish president, Mariano Rajoy, cannot speak in English.

Perhaps someone should have to explain him this history to understand what is happenning now in Catalonia.