At the World Knowledge Forum in Seoul last week, I had the privilege to listen to and chat with a number of experts on the situation on the Korean peninsula, meet many people of different ages, and even managed a side trip to the demilitarised zone (DMZ) which marks the location of the cease fire which brought an end to the Korean War in 1953. The South Koreans have built a tourist attraction around the site which includes an empty railway station that was supposed to connect the North and South, an observation platform and access to one of the four tunnels that the North Koreans had built in the 1960s under the DMZ.

At the World Knowledge Forum in Seoul last week, I had the privilege to listen to and chat with a number of experts on the situation on the Korean peninsula, meet many people of different ages, and even managed a side trip to the demilitarised zone (DMZ) which marks the location of the cease fire which brought an end to the Korean War in 1953. The South Koreans have built a tourist attraction around the site which includes an empty railway station that was supposed to connect the North and South, an observation platform and access to one of the four tunnels that the North Koreans had built in the 1960s under the DMZ.

Korea has been in the news for the last two years as the world has watched in wonder at the antics of Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. Kim started off the latest round of events back in the summer of 2017 by testing nuclear weapons and a ballistic missile system which could potentially deliver them to the United States.

President Trump responded with an impromptu speech in which he promised “fire and fury” that would send the country back to the “stone age”. The interchange and rising tension was greeted with dismay in Seoul which is 52 KM from the border and home to 12 million people not counting the wider metropolitan area. The border itself is heavily fortified on both sides although there is a strip 250 km long and 4 kilometer wide in which no heavy weapons are allowed called the demilitarized zone or DMZ.

Trump first visited Seuol in November, 2017 and since then has had 8 meetings with South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in and face to face meetings with Kim one in Singapore and one at the DMZ itself where he actually crossed the line giving de-facto recognition to North Korea’s border even though no peace treaty has been signed.

Trump first visited Seuol in November, 2017 and since then has had 8 meetings with South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in and face to face meetings with Kim one in Singapore and one at the DMZ itself where he actually crossed the line giving de-facto recognition to North Korea’s border even though no peace treaty has been signed.

In a gesture of good will, the United States has suspended joint military manoeuvre with the South Korean army although such activities are thought to be needed to keep the joint forces ready in case of war. For its part, North Korea has not tested a bomb or a ballistic missile since the summits began although it is routinely testing its short range missiles which could, for example, cause massive destruction to Seoul and threaten the South Korean army and the 28,000 U.S. soldiers and their dependents stationed in the country.

For Trump the engagement has been a complete success and he has declared his “love” for the North Korean leader who he now says has “great personality and is very smart”.

The consensus in Seoul last week was, however, that the initiative has so far achieved nothing of substance and in fact has elevated President Kim’s status as an international statesman. He has met with President Xi of China 5 times., was received by Valdmir Putin in Moscow and has held eight meetings with South Korea’s President Moon and even made a declaration calling for unification and complete de-nuclearization.

One South Korean economist, Byung-Yeon Kim, felt that full and fast normalization was unlikely as was a return to the fire and fury rhetoric and a possible war. In his view, the most likely scenario was to see a gradual opening up of North Korea’s economy in line with a step by step approach to the freezing and dismantlement of its nuclear program.

What I found very interesting is that no one I spoke with could see a scenario where the North would be economically and politically absorbed by the South much like East Germany was during German unification in 1991. The thought is that the East German experienced was a terrible burden for the West Germans and it would be even more difficultly were it to happen in Korea.

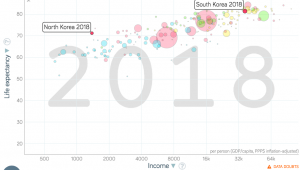

Professor Kim pointed out that East Germany had a population about one quarter of the west and in economic terms had a GDP per capita which was about half. North Korea has about half the population as the South but its GDP per capita is 30 times less.

While over time most people I spoke with could see the logic of unification, no one believed that South Korean citizens want to pay for it and many are concerned that any money sent North would be stolen by corrupt government officials.

In addition to the geo-political division of the country, the three other issues being discussed last week was the trade war between the U.S. and China, increasing tension between South Korea and Japan, and American insistence that South Korea increase its contribution to the cost of maintaining the U.S. presence in the country.

This year, South Korea will contribute $ 870 million to the effort but President Trump and Mike Pompeo are reportedly asking for $ 5 billion. During the conference I was struck by the number of times that American speakers tried to re-assure the mainly Korean audience that the alliance between the U.S. and South Korea was solid as a rock regardless of where the negotiation ended up.

The biggest unspoken fear was that Trump would agree to withdraw the American troops in another gesture of good faith to his new best friend Kim Jong-un.

Trumps new friend spends huge amounts of money on the fourth largest army in the world and has developed his missiles and nuclear weapons while his people are amongst the poorest on the planet. They have no free press or elections and are understood to live in a distopian police state.

To my relief, several retired and active American military officers told me that such an outcome was not possible in the medium term regardless of what the President tweeted as their were a number of checks and balances in place to prevent a sudden withdrawal.

I for one am confused by this President’s strong actions on China and the apparent appeasement of North Korea. As a counterpoint, the policy of the Obama administration was to isolate North Korea diplomatically until it agreed to dismantle its nuclear program.

I for one am confused by this President’s strong actions on China and the apparent appeasement of North Korea. As a counterpoint, the policy of the Obama administration was to isolate North Korea diplomatically until it agreed to dismantle its nuclear program.