Last week there were Parliamentary elections in Poland and municipal elections in Hungary which could be interpreted as a check on the populist governments in both countries although there appears to be a deeper process going on which has to do with the benefits of the transition to democracy and the European Union which began some 25 years ago.

The news reports about the Polish election discuss how Jaroslaw Kaczyński’s Law and Justice party has held on to its majority in the lower house but narrowly lost control of the Polish Senate. Law and Justice has been accused by the European Union of stifling the courts and pursuing a populist, anti democratic agenda. In the campaign, the party came under criticism for its tough stance against the gay and lesbian community in the country.

With respect to Hungary, the news was all about how Gergely Karácsony managed to unite the opposition to Viktor Orban and his Fidesz and win election as the new mayor of Budapest last week. I was told that Karácsony means Christmas when I was in Vienna last week so perhaps the new Mayor is a present for the citizens of the capital. The opposition managed to win 13 of Hungary’s biggest cities last week.

Just a few days after the election of Karácsony, the European Parliament voted to sanction Hungary for supposedly reducing freedom of the press and the independence of the judiciary. Orban hit back saying the sanction was petty revenge for his tough stance against middle eastern refugees.

30 Years for what?

Concern about the governments of Poland and Hungary are widespread amongst liberal Europeans who see danger in their populist rhetoric and focus on the personal leadership produced by men like Poland’s Kaczyński and Hungary’s Orban. For Attila Agh, a professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, the issue is not so much what these populist politicians are doing or not doing but why they were elected in the first place. In his view, the election of populist leaders and the formation of the Visegrad Group (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) is all about a deep disappointment on the part of the people of these countries with respect to their expectations after the fall of the iron curtain and their adhesion to the European Union.

1989 brought the prospect of Freedom to Central Europe. Orban, for example, formed Fidesz as a protest vehicle against communist rule and was a champion of Democracy. He became Prime Minister Hungary after the elections of 1998 but was then voted out of office in 2002. According to a Hungarian executive who I met with last week in Vienna, Orban is not an autocrat but learned from that experience that a politician must appeal to the hearts of the people and not so much to their minds.

1989 brought the prospect of Freedom to Central Europe. Orban, for example, formed Fidesz as a protest vehicle against communist rule and was a champion of Democracy. He became Prime Minister Hungary after the elections of 1998 but was then voted out of office in 2002. According to a Hungarian executive who I met with last week in Vienna, Orban is not an autocrat but learned from that experience that a politician must appeal to the hearts of the people and not so much to their minds.

In its own report on the transition to democracy and EU membership in Central Europe, the EU recognizes that the transition has brought enormous change to the countries of the region as well as some disappointment Professor Agh says the results have been controversial and road to prosperity a “bumpy” one. His view is that while there have been attempts at political and economic change, social change happens slower and that this is one of the causes of democracy to suffer.

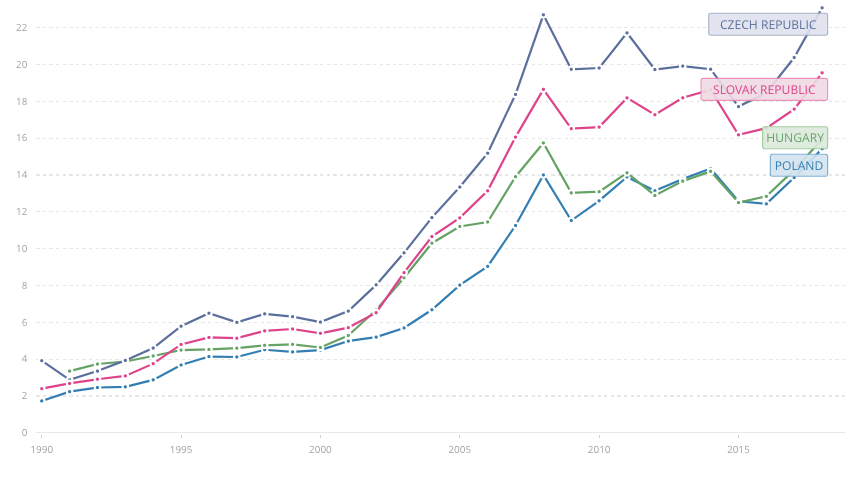

Economically, the region has done well over these 30 years with GDP per capita increasing sharply all across the region. The biggest gains have occurred in the capitals of the different countries and in some cases other large cities. In many ways the countryside is the same as it ever was or perhaps even worse than people remember in earlier times.

In Hungary, Fidesz lost in Budapest and 12 other cities but is likely to continue to dominate in the countryside. In Poland the election results in Warsaw itself also confirmed this urban and rural split. According to the Polish Electoral Commission, at the national level Law and Justice received 43.6 % of the vote compared with 27.4% for the largest opposition group. In Warsaw itself, however, the numbers were reversed with the PO winning 42.0% compared to Law & Justice which only had 27.5%.

Central Europe has always been either a bridge between East and West or a buffer zone for either side. While I applaud efforts by Western Europe to keep the governments of the region firmly anchored to the democratic values of Europe, the policy framework needs to make sure that the people in the countryside feel the real benefits of being part of the West. If not, they will continue to look for easy solutions to complex problems and vote for politicians like Viktor Orban and Jaroslaw Kaczyński who speak to their heart.