Of the many geopolitical issues that the new Biden/Harris administration needs to pay attention to, the situation in South East Asia and the Pacific may be the most difficult. The coup in Myanmar or Burma as it was formerly known is only part of the larger story which is about a struggle between China and the United States for regional leadership.

To fully understand where things are going, it is essential to recall that for hundreds (if not thousands) of years, China dominated the region.

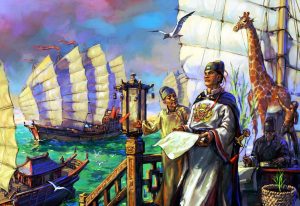

China’s leadership position dates back to wars of conquest in Indochina and on the Korean Peninsula and the seven voyages of Admiral Zeng He at the beginning of the 14th century. Other countries would pay tribute to China and their representatives would kowtow to the emperor in a sign of submission.

This system was first upset by the fall of the Ming dynasty in the 1640s and then the invasion of China in 1839 by the British in what was the first of the so-called Opium Wars.

The Opium wars eventually led to the collapse of the Qing dynasty, the Taiping rebellion, invasion by Japan, and the Chinese Civil War. In China, the 110 years between the first invasion and the victory by the communists in 1949 are referred to as the century of humiliation.

After World War II, the United States moved into the vacuum left by the defeated Japanese empire and exhausted European powers who had established colonial governments in many of the countries that had been occupied by Japan during the war. The first test of American resolve was the Korean War fought in the early 1950s that led to the current division of the country along the 38th parallel.

The second was the war in Vietnam in which the U.S. attempted to prop up the government of South Vietnam against the communist regime in the North that was financed and supported by the Soviet Union. After the North’s victory in that war in 1975, Vietnam emerged as the leading power in South East Asia until it was invaded by China in 1979 in order to force Vietnam to cease its involvement in the internal affairs of Cambodia.

In 1967, before Vietnam would turn into a full-blown conflict, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand founded the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to promote regional security and trade.

After the Vietnam war, American policy in the region consisted of its unwavering support for Japan and Taiwan and the maintenance of a system of military alliances and trade agreements with other countries.

In parallel, ASEAN expanded its membership to ten countries in the region including Vietnam in 1995 and gradually moved away from its former US-centric outlook to include cooperation with Japan, South Korea, and China.

In parallel, ASEAN expanded its membership to ten countries in the region including Vietnam in 1995 and gradually moved away from its former US-centric outlook to include cooperation with Japan, South Korea, and China.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. responded to a series of specific issues and crises such as the end of Ferdinand Marcos’ regime in the Philippines and the eventual disagreement with the government of Corazon Aquino which led to the closure of the U.S. military bases in the country.

During this time, China enjoyed a period of unprecedented economic growth beginning with Deng Xiaoping and continuing to the present day. As part of its expansion, China has worked tirelessly to re-establish its traditional role at the center of Asian trade and geopolitics.

The Trans Pacific Partnership began as an agreement between four countries in 2006, In 2008, the United States expressed interest in joining and that idea was picked up by the incoming Obama administration which worked for years to expand the agreement to 11 countries and finally completed it in 2015.

In parallel with the negotiations of the TPP, the Obama administration announced that it would change the focus of the U.S. foreign policy and military deployment under the banner of what it called a pivot to Asia.

Both initiatives were designed to contain China’s expansion in the region. The TPP was essentially an offer to the countries of Southeast Asia to join the U.S., Mexico, Peru, and Chile in an enormous marketplace for goods and services. It went hand in hand with the pivot to Asia designed to contain China militarily and be prepared for Chinese aggression in the South China Sea and even a possible invasion of Taiwan.

Donald Trump made opposition to the TPP an essential part of his election campaign arguing that it was a bad deal for American workers. His administration withdrew from the TPP and raised the rhetoric with China kicking off a trade war.

China meanwhile launched a number of ideas to build its own influence in the region. The One Belt, One Road initiative was launched 2013 and has essentially financed dozens of infrastructure projects across the region to connect China and its neighbors with ports, highways, and railway lines in a modern version of the ancient silk road.

Another is an alternative trade arrangement with the countries of the region called the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership or RCEP. RCEP was signed in 2020 and includes the ten countries of ASEAN as well as China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

An example of the success of China’s policy can be seen in the Philippines where its President Rodrigo Détente makes no secret of his preference for Chinese largess versus American condemnation for his approach to human rights and law and order.

Myanmar is, of course, part of RCEP and shares a border of over 2,000 KM with China. Although the Chinese government has denied its direct implications in the recent coup, it has used its veto in the UN Security Council to block condemnation of the situation.

How the U.S. can influence events almost 14,000 KM away would be difficult at any time. In light of the region’s history and apparent shift toward China, it will be extremely difficult.