Ever since the United States Environmental protection Agency blew open the emissions scandal involving Volkswagen, the diesel engine, named after its inventor, Rudolf Diesel has been under pressure around the world. At the moment, a number of countries and cities have announced bans on diesels in the near future and the market share of diesels continue to fall across Europe.

Ever since the United States Environmental protection Agency blew open the emissions scandal involving Volkswagen, the diesel engine, named after its inventor, Rudolf Diesel has been under pressure around the world. At the moment, a number of countries and cities have announced bans on diesels in the near future and the market share of diesels continue to fall across Europe.

At issue is a conflict between the goal of decreasing fuel consumption and the production of greenhouse gasses on the one hand and local air pollution on the other. Diesel engines, which use compression to ignite fuel, are more efficient than gasoline engines and thus use a bit less fuel to drive the same distance thus producing less Co2. Because of this, European governments have been adding less taxes to diesel fuel for a generation and Europeans have been paying a bit more for the cars in exchange for better fuel economy.

The problem is that diesel engines also produce small particulates, which are carcinogen as well as Nitrogen Oxide and Nitrogen Dioxide (NOX) which impact human’s respiratory and cardiovascular systems. In its latest policy assessment on NOX regulations, published in April 2017, the EPA reiterated its conviction, based on a meta review of all available studies, that there was a clear casual relationship between NOX and a probable link to heart disease.

At the heart of the Volkswagen scandal was the difficulty of meeting the increasingly strict emissions requirements of the U.S. and Europe using existing technology without adding inconvenience, cost, weight or reducing the power of modern diesel engines. What Volkswagen and other manufactures have done is to program the cars to operate in one way when the cars are being tested by regulatory authorities and in another way when driven on the road by consumers. The defeat device is actually lines of computer code embedded in the engine control unit of the cars.

While it seems that the law in the US. and Europe is written in a similar way, the regulations and legal precedents are very different and the European car companies believe that what they have done is not illegal in Europe. According to the Guardian, all car companies use such computer code in one way or another in Europe.

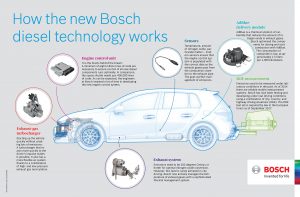

Meanwhile the company that built the engine control units for Volkswagen, Robert Bosch, has announced that it will no longer include such defeat device code into any of its products for any clients. Rather than conceding the death of diesel technology, however, Bosch also claims that it can meet even the most stringent requirements using its current technology.

A German colleague told me that their is currently a discussion raging in the press and social media in Germany is all about whether the NOX requirements are actually sensible in the first place. In his view they overstate the human health hazards involved and use measurement protocols which go further in overstating the problem.

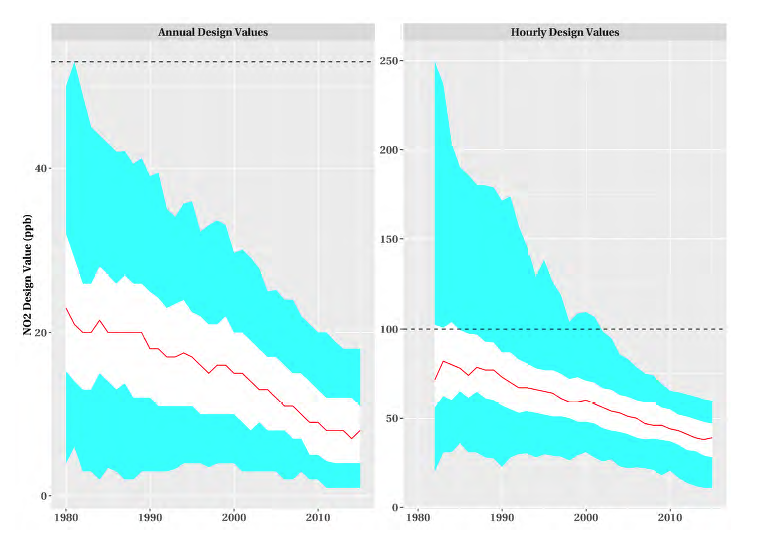

The good news for the U.S. is that the impact of tighter regulations appears to have worked. The 1970 Clean Air Act first introduced the idea to limit emissions from cars and trucks and put a limit of 3.1 grams per mile in place in 1975. For cars, that limit was reduced to 2.0 gpm in 1977/79 and then again to 0.6 in 1994. In 2004, the limit became 0.07 gpm and it is set to go down to gradually go down 0.03 in 2025.

The chart below shows the declining levels of NOX detected in the U.S. and I believe the EPA when it claims victory in this fight. The charts show falling levels of NOX in parts per billion both in terms of the annual average and in peak exposure over an hour.

What is really at stake is the future of personal transportation. Car companies, including Volkswagen, are currently rushing to get electric vehicles to market and to convince their consumers and shareholders that they, and not upstarts such as Tesla, are credible parters for the future.

While Volkswagen has paid $25-30 billion in fines and damages in the U.S. and a few of its executives are currently in Jail, I am not sure that the industry has yet to realize how badly they have been misleading the public. Perhaps if they really want to stay in business for the medium term, they must first understand that regulators in the U.S. and a segment of the public no longer accepts their excuses and misrepresentations.