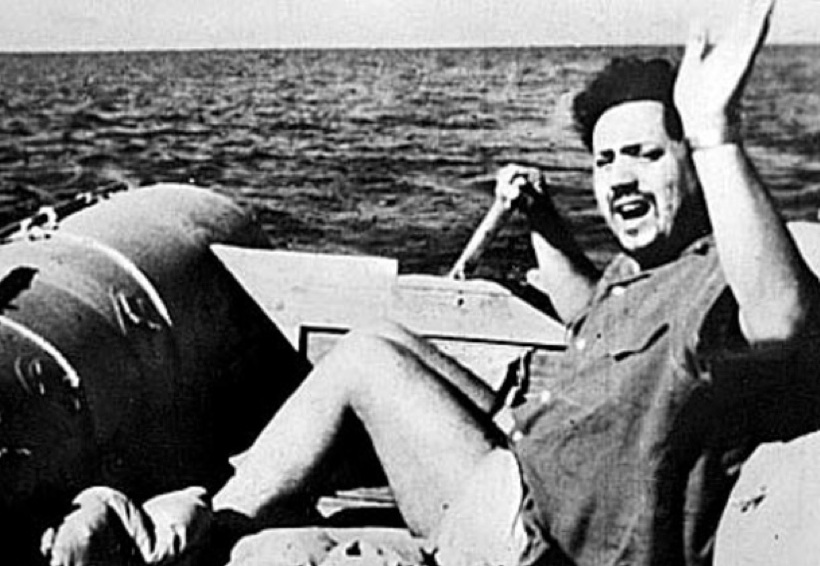

In 1953, French doctor Alain Bombard (1924-2005), concerned about the great many shipwreck victims he was treating in the Boulogne-sur-Mer area, set out to find a method that would allow someone in a small boat to survive a long ocean voyage. Finally, after many months of study at the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco, he decided it was possible for a castaway to survive by only eating plankton and drinking the water from the fluids of raw fish and from the sea (in small doses) in times of little rain.

The scientific community was skeptical with Bombard and some people even thought he was crazy. To prove his theory, he decided to sail alone in a small boat on the difficult journey from Tangiers to Casablanca, the Canary Islands and the Antilles. He sailed without a radio or outside help. All he had was a logbook in which he noted down all the things that happened to him during the sixty-five-day crossing.

Why are we discussing Bombard and his risky adventure?

Because he jotted down some ideas in that logbook that have a direct connection to the Europe of today:

“[of all the risks and dangers] you have to overcome the most important one; you have to destroy that deadly despair (…). Thirst kills before hunger, but despair is even faster than thirst..”

His handwritten notes contain a brief but lucid diagnosis of our worrisome reality: despair.

In the years before the recession, Western society boasted about how well things were going. Accumulating wealth and fortune made us feel “alive” and let us believe we were paving a road that was wide enough to think that our lives could not be restricted by anyone or anything. But the truth is that our society has bled to death. It didn’t die from hunger or thirst, but from a lack of hope. Just ask the people you know when they think the recession will end. Quite a few of them will say, “At this rate, probably never.”

The big thing we’re missing is not excess, wealth or a well-paid job. It’s the awareness that people are being treated as mere tools with no soul or specific weight, as simple cogs in the gear system of a machine that is not subject to human growth through professional work, but to the empire of money and cutthroat mercantilism characterized by endless struggle and competitiveness.

Because what really matters is not the undefined wealth of individuals considered abstractly, but the set of social conditions that allows groups and their members to fully and easily achieve their own perfection. That is the common good. Experience shows that good results do not come from pursuing only our own interests with no concern for the good of society.

But what does that common good consist of?

For Jacques Maritain, the common good “is not only the collection of public commodities and services (the roads, ports, schools, etc.), which the organization of common life presupposes; a sound fiscal condition of the state and its military power; the body of just laws, good customs and wise institutions, which provide the nation with its structure; the heritage of its great historical remembrances, its symbols and its glories, its living traditions and cultural treasures. The common good includes all of these and something much more besides, something more profound, more concrete and more human. For it includes also, and above all, the whole sum itself of these. It includes the sum of all the civic conscience, political virtues and sense of right and liberty, of all the activity, material prosperity and spiritual riches, of unconsciously operative hereditary wisdom, of moral rectitude, justice, friendship, happiness, virtue and heroism in the individual lives of its members. For these things all are, in a certain measure, communicable and so revert to each member, helping him to perfect his life and liberty of person. They all constitute the good human life of the multitude.” (The Person and the Common Good, 1947)

And Benedict XVI wrote in the encyclical Caritas in Veritate (2009): “The great challenge before us, accentuated by the problems of development in this global era and made even more urgent by the economic and financial crisis, is to demonstrate, in thinking and behaviour, not only that traditional principles of social ethics like transparency, honesty and responsibility cannot be ignored or attenuated, but also that in commercial relationships the principle of gratuitousness and the logic of gift as an expression of fraternity can and must find their place within normal economic activity.”

What can we do?

We can show concern for people based on what they are and not what they are worth (human relations cannot be based on mere profit and loss calculations). Otherwise, we run the risk of rejecting any kind of hierarchy of human needs and that creates confusion between real need and unchecked desire.

We can start with the things around us. Economic problems will probably continue, but reaching out when someone is in need could be like the gentle rain that castaways long for. It’s the first step.

I agree with you, if we dont get back the human dimension… we are lost. Very interesting. But, it is possible?

It depends upon ourselves. Think about how you contribute to common good. There are not a magic spell to fix all our problems. But, in my opinion, the first step is do our best (what is close to our hand).

Nice analogy to use Bombard’s insights to reflect on a common but unfortunately real dilemma in our western culture. How the accumulation of wealth and fortune de-humanizes our societies and foments the now often cited income/wealth inequality. There are no ready solutions to this real world problem but as De las Heras notes big changes can be achieved by making small steps. At the end we are all in the same boat/earth and we need to make sure that we don’t decouple our materialistic pursuits from our humanity.

A diferencia de Bombard, que se preparó a conciencia para su travesía (estudio de las condiciones climatológicas, el tipo de alimento a consumir, las vitaminas necesarias, etc.), nuestra sociedad emprende el “viaje de su vida” (la vida) sin ningún tipo de previsión.

Y siguiendo con la metáfora, el “aquí y ahora”, el “corto plazo” y el “yo” son piedras demasiado pesadas que si no las arrojamos no saldremos a la superficie.