Last week I led a discussion among public managers on the ethics of their job, during a session of a public leadership program at IESE. I want to share with you the preliminaries of our conversation and the questions that finally came up.

- First of all, the owner of the public institutions is the people (as Cicero wrote: Res publica, Res Populi: the public things –the commonwealth, the Republic– belong to the people). Public servants are always serving others interest.

- We may expect and tolerate egoistical behaviour from businessmen, but we do not accept a politician or civil servant that shows himself bound to an interest other than the public.

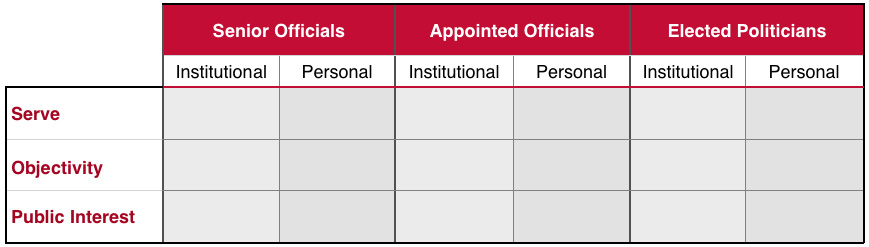

In contrast, the spirit of legal texts around the world is focused onservice, objectivity, public interest. Three concepts full of moral connotations that cannot be reduced to any merely technical procedure.

- Service is the central concept, and it is explained by the other two:

- public interest –excluding preliminarily both particular and private interests–, and

- objectivity –meaning the opposite to subjective thinking influence by emotions or interests other than the desire to serve the constituencies. This is usually expressed by the obligation to follow legal norms in exercising public power: the rule of law.

This public service is to be carried out in a different way depending on the legal position of the public manager. The main difference in the nature of the office is defined by the immediate authority that transmits the power and competence, and the correspondent margin for discretion that is left by law in interpreting the content of public interest in each case. We distinguished between:

- Senior officials, exercising competences but with not political appointment;

- Appointed senior officials, who depend on the trust of elected politicians.

- Elected politicians. These latter are bound to the public interest, and exercise legal competences, but with much wider discretionary powers.

Politicians of all kinds used to have a personal career within political parties or are linked with them, so they find themselves in a permanent conflict between two mentalities: statesmanship and party mentality–biased and elections oriented. Ironically, even in developed countries, public servants of these three levels are usually depicted as “lazy, well connected and corrupt”, a participant said.

A third dimension was added in order to analyze the specific ethical requirements of each position: the difference between institutional and personal ethics.

- For civil servants the institutional ethics are very strong and used to be well established by law and codes of conduct. This is more difficult when it comes to politicians.

- But in both cases there is always room beyond legal prescriptions for arbitrary decisions that cannot be controlled by legal means, what some call “the power of sergeants”. This is just another reason for considering that character and personal virtues–so important for personal performance–should also be part of the equation when fostering highly ethical standards in public officials–which is required for the service to the public interest.

Considering all these ideas a set of questions arose, that the reader may find interesting to think about:

- What requirements will you demand from each one of the three levels of public managers, as requirements for serving, acting with objectivity and considering the public interest?

- What kind of human being will behave following such high moral standards with no outstanding economic incentives?

- How can society foster those moral personalities, shaped by civil virtue and not exclusively by individual interests?

- Could we think of other human activities –business in our case– as a service to others beyond the constraints of emotional biases and material interests?

Thanks ! it’s great