While TV streaming wars fill headlines, audio battles remain in the background and are as cutthroat as ever. Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music are ahead of the pack, with YouTube Music and Pandora following their lead. They offer similar services, with slightly different prices. In such an undifferentiated market, it seems that only the first mover has the advantage to remain ‘first.’ But when those services want to grow, coming in first or second is not enough. The solution? For now, discounts and gifts.

At the moment, these five services crowd the market—all with similar offers. Pandora came in first. Launched in 2000, Pandora began as a paid service but quickly opened the platform to non-payers and switched its business model to rely heavily on advertising. But after 2016, the company has made a push to increase its paying subscriber base. Although Pandora was the first-mover, it has not enjoyed the first-mover benefits. At the moment the service has 6.9 million paying subscribers—millions fewer than YouTube Music, Amazon Music, Apple Music and, of course, Spotify. Reasons for Pandora’s failure abound but the most important one is that the service did not include on-demand music until 2017. By then, Spotify had already taken ahold of the market. Pandora was the first online music platform, but Spotify was the first service to offer what the customer wanted whenever he/she wanted it. On-demand has been a must since then.

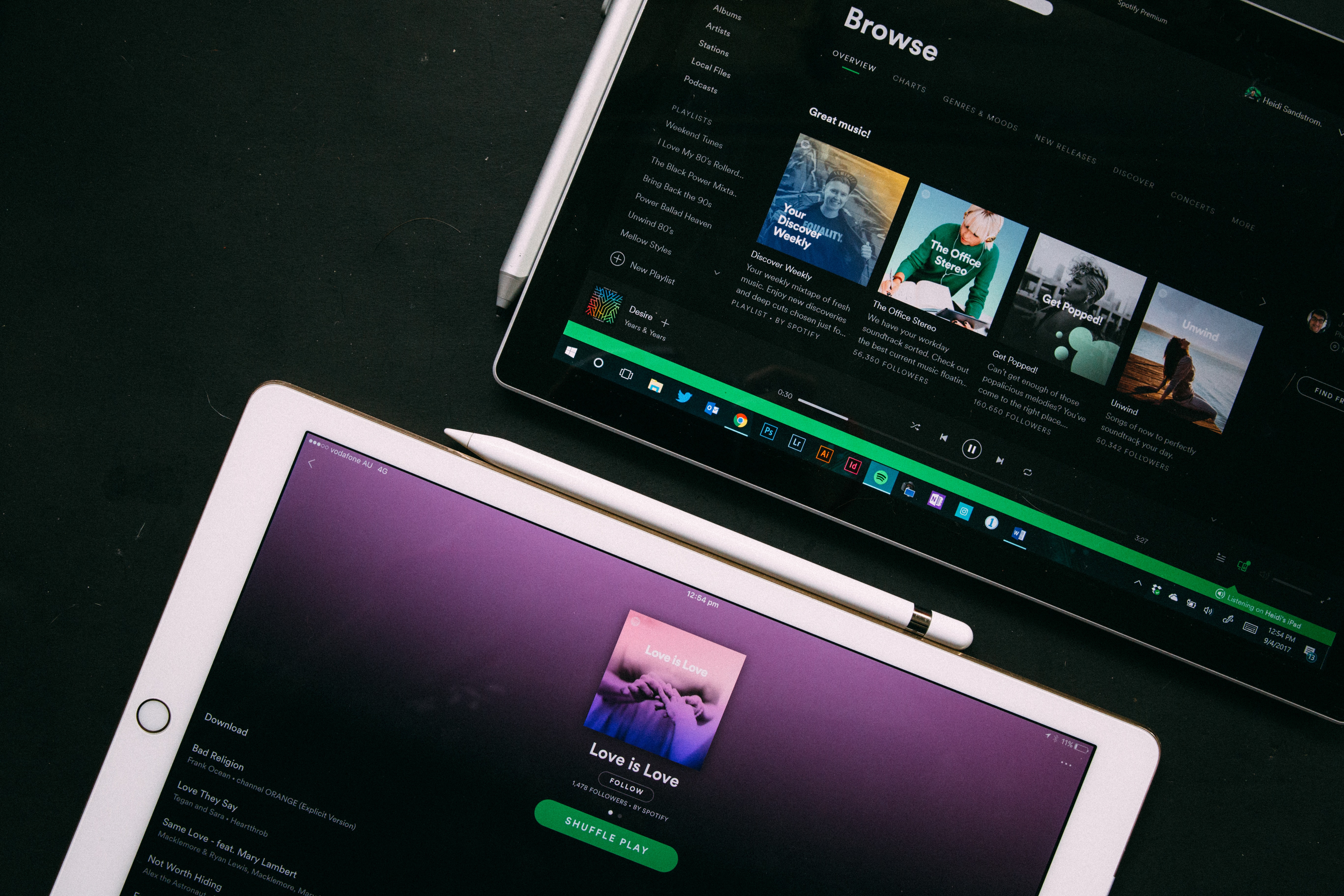

Founded in 2006 and launched two years later, Spotify has enjoyed the ‘first-mover’ benefits so far. At the moment, the service has over 248 million users, with 113 million paying subscribers, according to company’s data. Although it offers a free ad-based registration, since its inception, Spotify has prioritized a paid-subscription model—$10 for an individual subscription. Spotify’s uniqueness, very much like Netflix, was that customers could listen to anything they wanted at any moment, instead of having to wait for a song to pop up on the radio. By 2011, Spotify already had 2 million paying subscribers; by 2014, the number had grown to 40 million, and two years later, to 100 million. Although by 2015, Apple Music had launched its streaming service, Spotify was already ahead of the pack with a large market share.

Apple Music was actually launched in 2015, but this was not Apple’s first incursion into the world of music. The media player iTunes was founded in 2001, and iPhone and iPad owners used it to create lists and reproduce their own music on their devices. It was a success, but the company was slow to add an online streaming platform to it. Still, Apple Music already had 60 million subscribers in June 2019, four years after its launch. The reason for its growth is simple—Apple has over 1.4 billion active users. Moreover, its subscription fee is lower, only $4.99 per month. Despite these advantages, especially for iPhone users, Spotify is still ahead thanks to its first-mover advantage—very similar to the success of Microsoft computers. Once MacBook computers were available and cheap enough for offices, most companies were working with Microsoft devices and a large ecosystem of software developers, IT technicians, and system implementors for that platform already existed. It became expensive to change from one computer system to the other, and most people in the same office were already using Microsoft. The company had the advantage of network effect thanks to its first-mover status. Unfortunately, unlike with computers, the competitive advantage provided by the size of the network is much smaller for music streaming services. Network effects matter—if most of the people you share music with use the same service, it’s easier to trade playlists, for example,—but the marginal cost of changing services is not as high as with computer systems.

The massive online retailer’s music platform, Amazon Music, occupies the third place in the rank, with 32 million subscribers. The service is very new—Amazon Music Unlimited, the online streaming platform, was launched in 2016 in the US. However, the online retailer’s subscriber base is growing fast thanks to its large Amazon Prime subscriber base and also to its intelligent speakers, Alexa, which encourages users to buy a subscription—$8 for Prime members, $10 for non-members. As Apple, Amazon has the advantage of a wide infrastructure and a strong market penetration. With over 105 million Prime subscribers in the US, the platform has immense potential for growth. Finally, Google’s YouTube Music, launched in 2015, is the fourth most used service in the music streaming platform market, with 15 million subscribers. The Music feature has not grown as fast as the other platforms, in part because Spotify already fills the market, in part because listeners are used to a free YouTube platform.

Although in the early 2010s the differences between the platforms were more obvious—some did not offer on-demand music, others were launched later,—in 2019 those differences have mostly disappeared. They all offer similar content, similar music options and similar service. They provide, in similarly laid out apps, over 50 million songs in forms of lists. None of them have exclusive rights to singers or albums, and none of them offer previews. It’s true that Spotify has struck licensing deals with independent artists that had no contracts with record labels. But, as reported by The New York Times, those contracts do not include exclusivity and artists are free to license their songs to other services like Apple Music.

The result is that you can listen to The Beatles and David Bisbal on those five platforms, which is great for consumers. Unlike the TV streaming business, in which, the real fight is for content, music services struggle to keep their preeminence. In this context of undifferentiated products, marketing strategies resemble those of supermarket’s white labels. They try to gain subscribers by lowering prices, offering discounts, or gifting products. Since October, Spotify has been giving away Google Home Minis (Google’s AI speakers) with individual and family premium subscriptions. Amazon, however, is doing the same. With an Amazon Music Unlimited subscription, buyers can acquire an Echo Dot for 99 cents. In Amazon’s case, the speakers will constantly tell subscribers to buy the subscription—a reinforcing tactic. But so far, this is one of the few differences consumers perceive between the brands—except the aforementioned network effect.

This strategy may make sense in the short-term, but it won’t hold for long. Music streaming platforms must give users a reason to pay for their unique service, that is, exclusive content. If not, the idea that all music and all albums have the same value will settle in. Two of the arguments against content-exclusivity in the music streaming industry, as reported by Rolling Stone, are the following. On the one hand, users don’t listen to old albums as much as new, so having exclusive rights to The Beatles won’t make a difference in terms of gaining new subscribers. On the other, the record industry already sells the rights to those platforms to increase the reach of their content. In this way, it reduces the risk of piracy, which would harm their business. From the viewpoint of recording companies, there’s no need to change the strategy, unless they gain something. Spotify’s strategy to license music from independent artists is a good start, but it would make more sense if the service retains exclusivity rights. However, that will be a hard choice for starting musicians, who want to get their content out there.

While Netflix, Hulu, HBO, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ are killing themselves for the rights of old shows like Friends and are investing millions of dollars in developing new high-quality movies, the music industry remains stagnant. Until now, the first-mover advantage has worked. Spotify remains on top thanks to network effects and its on-demand content. However, this can quickly change. The company lacks the infrastructure to compete with Amazon and Apple—both tech companies could end up offering the same as Spotify for a lower cost, through an envelopment strategy. If the company cannot fight through distribution, it should remember that content still makes the difference.

La información de este articulo es altamente valiosa y no se debe dejar de lado todo el mensaje que deja luego de leerlo.

More informative

informative

I almost agree, although record companies make a lot of money through paid and unpaid advertising produced by their own consumers.

Someone else is tired of all the ads that come to you for 3 months for free, try it during such … This is already a lifeless …

regards

Keep it up. thanks

This is a great piece of information. I agree, despite the fact that record organizations rake in money through paid and unpaid promoting created by their own purchasers.

I think it’s not bad to promote yourself. Whi will promote you if you don’t. But on the other hand content quality is the most important factor which must be kept in mind.

I stick to spotify. Maybe not perfect, maybe not all the music I need, but price is OK, I take advantage of the family plan, works in all platforms and I already have all my playlists there. It quite difficult that I move to any other alternative.

Six channels devoted to various music video genres, including ’80s and ’90s music for us olds (plus channels playing hip-hop, country, and party jams.) Programming will come from Loop, a new-ish company that serves up on-demand video playlists via its mobile and TV apps, and is already doing the live linear thing on Roku Channel competitor Plex.