It’s a common catchphrase among the right that the left has captured social media. They argue that the platforms are only banning or tagging content from specific right-wing figures such as President Donald Trump, while not taking issue with leftist commentators. After the defeat of Trump in the elections, millions of users have decided to leave Twitter and Facebook in favor of the new social media app Parler, as they felt that their voices were being curtailed. Parler lacks content moderation strategies similar to the mainstream platforms, opening the door to any conversation, including hate speech. At the same time, its proponents argue that Parler is what a network should be like, providing only the platform itself without taking a stand in the content and letting users moderate themselves. But, in the era of misinformation, can we manage our content?

Launched in 2018 by engineers John Matze and Jared Thomson, the social networking service garnered more than eight million users by mid-November, doubling the number of members it had before the elections, reports the New York Times. Some conservative personalities such as Fox commentator Sean Hannity or Senator Ted Cruz from Texas announced they would be active on Parler, angered at how Twitter had reacted to the election results. Although the social media app started with more extreme right users such as Alex Jones from Infowars—many of which had been banned from Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube—Parler is gaining traction among mainstream conservatives.

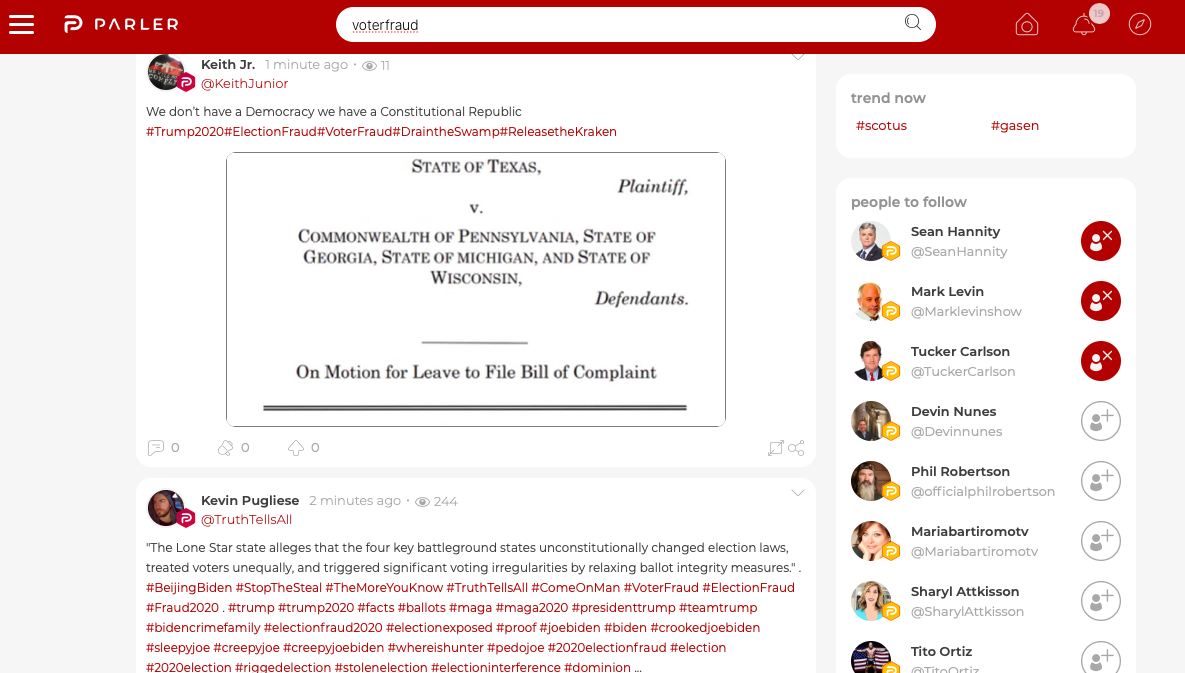

The move comes after Twitter and Facebook ramped up their misinformation monitoring strategy since the summer months. In June, Twitter started tagging some of Trump’s tweets as dangerous or lacking information. For example, when the Black Lives Matter movement erupted in June, Trump responded with a tweet saying, “when the looting starts, the shooting starts”—a comment made by Miami’s police chief in response to the 1967 protests, fueling state violence against mainly black demonstrators. Twitter immediately tagged the tweet with a notice saying that the post glorified violence, without deleting the post itself (read The limits of freedom of speech.) During the elections, social media platforms increased the number of tagged posts, especially when it concerned voting. Trump and its affiliates released many posts saying the elections had been fraudulent and won them if one only counted the real votes. This, as the Justice Department itself stated and the Supreme Court ratified, lacked all evidence. Twitter quickly tagged Trump’s tweets with a note saying it was misinformation. Besides, users could not retweet those posts. At the same time, Twitter and Facebook were deleting hundreds of social media accounts that supported the alt-right conspiracy theory QAnon (read How the post-truth world led to QAnon). Conservative users were incensed with Twitter and Facebook’s use of tags, as they felt right-wing politicians were disproportionately targeted. As such, since early November, there has been a substantial migration among conservatives to Parler.

Although similar to Twitter, Parler has its own tweaks. For instance, the app lets users post texts with up to 1,000 characters. And unlike any other major social platform, the app does not collect data from its users as it does not want to surveil them. It lacks an algorithm that shows its members targeted content, and thus, the posts are shown on the feed in reverse chronological order. Not collecting user data implies that Parler’s ads are not behaviorally targeted, as those of any major online service. This may prove problematic at some point, as the ads will be less effective, but at the same time, it shows a specific approach to the relationship between members and Parler. It’s also a response to the fear of many users of being monitored by social media. However, Parler has an essential ingredient—a large investor. Rebeca Mercer, daughter of Robert Mercer, is funding the app. The Mercers are well known political donors to the right, having supported Breitbart News and Trump’s campaign in the past. The father, Robert, became wealthy thanks to his work at hedge fund Renaissance Technologies.

In the same line, Parler offers a non-censored platform, which means that all kinds of posts can be found, including those related to violence and pornography. Comments from supporters of QAnon also roam freely in the app. If hate speech becomes prevalent, Parler could see advertisers fleeing the platform.

Parler’s approach to social media platforms is linked to the idea that users can moderate their own comments and that the networks must only provide the infrastructure for it. The platform advertises itself as follows:

“Speak freely and express yourself openly, without fear of being “deplatformed” for your views. Engage with real people, not bots. Parler is people and privacy-focused, and gives you the tools you need to curate your Parler experience.”

This was also the view behind Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA), which states that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” Platforms were regulated as services, not publishers, as they were not expected to edit content. With this in mind, Trump designed an executive order (EO) to limit the 230 section arguing that all social media platforms should remain neutral, given that a few monopolies control most of the country’s speech. The discussion is very much alive, with both proponents and detractors of the platforms’ curation strategies. But, is highlighting misinformation and banning hate speech really an editorial decision? Or is it more in line with preserving the health of the public discourse?

From our perspective, social media platforms do have a responsibility to ensure basic standards are met, such as making sure hate speech and misinformation are not pervasive on the site. That’s not editorializing; it’s just preserving the health of democracy. The specifics of how those strategies are implemented are up for debate. For Parler, content moderation is out of the question arguing it leads to hate—“Biased content curation policies enable rage mobs and bullies to influence Community Guidelines.”

However, Parler is more than a response to the conservative outcry against social media’s censorship. The app is also a reaction to the monopoly of social media giants. As the Wall Street Journal reporter Keach Hagey says on the outlet’s podcast, users are tired of feeling they have no way around tech companies. We have yet to see how Parler evolves. Still, without any content moderation, Parler runs the risk of becoming a home for hate speech, racism and misinformation.

this post is very informative. i learned lot of information from this site. article is nicely explained and easy to understand. thanks for sharing this valuable information from this post. keep it up

So hate speech and conservatives go hand in hand?

Grate post. Thanks for sharing!

As the Wall Street Journal reporter Keach Hagey says on the outlet’s podcast, users are tired of feeling they have no way around tech companies. We have yet to see how Parler evolves. Still, without any content moderation, Parler runs the risk of becoming a home for hate speech, racism and misinformation.

On the web, I could view the clay. Thanks for reading so far!! I’d like to thank you!! I’ve really loved this part.

this post is very informative. i learned lot of information from this site. article is nicely explained and easy to understand. thanks for sharing this valuable information from this post. keep it up

Great job. Thank you!

Thank you for your useful article